Vol. 41 (Issue 09) Year 2020. Page 7

Vol. 41 (Issue 09) Year 2020. Page 7

AFANASJEVA, Olga 1; VOZGOVA, Zinaida 2; FEDOTOVA, Marina 3 & SMIRNOVA, Marina 4

Received: 17/09/2019 • Approved: 03/03/2020 • Published: 19/03/2020

ABSTRACT: This study presents critical thinking as a specific type of activity in education. The focus of the research is on the content and structure of professional critical thinking (knowledge, skills, and dispositions) as one of the goals of professional training in pedagogical universities with much attention paid to the ways students and teachers conceptualize this phenomenon. The results of the study allow putting forward some ideas concerning understanding and conceptualization of professional critical thinking as a part of the teacher’s professional competence. |

RESUMEN: El objetivo del estudio es conocer el contenido y la estructura del conocimiento, las habilidades y las disposiciones del pensamiento crítico profesional como uno de los objetivos de la formación profesional en las universidades pedagógicas, prestando mucha atención a las formas en que los estudiantes y los maestros conceptualizan este fenómeno. Los resultados del estudio permiten presentar algunas ideas sobre la comprensión y conceptualización del pensamiento crítico profesional como parte de la competencia profesional del maestro. |

In responding to the challenges of a fast-changing digital reality modern education calls for new means and methods of professional competence development. For this purpose, it is necessary to enrich students in knowledge, skills and dispositions based on respect of their autonomy and preparing them for successful professional activity and for democratic citizenship (Hitchcock D., 2018). In this context, teacher professional competence allows critical thinking to be addressed.

However, the idea of relationship between critical thinking and teacher professional competence is becoming more obvious because of its alignment with the basic goals of Russian educational standards, according to which individuals are requested to ask questions, initiate new ideas, develop and expand their intellectual potential and apply it for professional problem solving (decision-making) in new situations. Consequently, as teaching activity requires a high level of analysis, synthesis and evaluation skills to make the right decisions and act on them, forming critical thinking skills has become one of the tasks of teacher training to foster improvement and promote success for students. Therefore, future teachers should be educated to be a good thinker because the outcomes of their services will improve the quality of individuals’ life. Moreover, professional critical thinking can lead to “empowerment, transformation and emancipation – in short, social action” (Dackenwald J.J., Merriam S.B., 1982). The place that researchers attribute to this phenomenon is defined by its value and depends, in its turn, on the conceptualization of this notion, which raised a long-standing interest.

The purpose of this article is to give a professional critical thinking conceptualization based on scientific literature analysis and to find out whether this interpretation correlates with students and teachers’ perception of this notion. We seek to identify “professional critical thinking” as a part of teacher professional competence, to describe its diverse understandings, to define its content and to provide empirical evidence regarding the attitudes of teachers and students to develop professional critical thinking skills of future teachers.

We start our investigation with the analysis of the notion “critical thinking”. There exist many variations on the definitions The great variety of interpretations of critical thinking may result in confusion about its concept. No wonder being multidimensional and complex this notion requires clarification. Due to the analysis of scientific literature, we have witnessed the shift from a widespread skepticism about the value of critical thinking skills to a demand that critical thinking matters a great deal for teacher professional competence. Nevertheless, the question how critical thinking skills operate to improve teaching practice remains a subject of debate. As a result, in the body of scientific literature, critical thinking is thought to be:

1. an ability to analyze the information objectively and make a reasonable judgement, to evaluate the research findings (Doyle A., 2019);

2. a process of questioning one’s assumptions , exploring new ways of thinking, forming solutions and acting on these solutions ( Garrison D.R., 1991);

3. as an action actively including identifying and challenging assumptions and exploring and imagining alternatives (Brookfield S.D., 1987);

4. as a perspective transformation which suggests that people moderate their individual behaviors reflecting on their assumptions (Mezirow J.,1991);

5. as a social activity in a community of physically embodied and socially embedded inquiries with personal voices who value not only reason but also imagination and intuition and emotion (Thayer-Bacon B.J., 2000). In other words, critical thinking doesn’t occur unless there is a sharing and interacting with others (McPeck J.E.,1990). Moreover, it is the dialogue that is capable of generating critical thinking (Freire P.,1989);

6. as a reflection of facts, phenomena in essential relations and connections that are specific for a certain type of professional activity (Gilmanshina S.,Kodekov G., 2018);

7. as optimal way which promotes human professional activity that is implemented in searching for and finding conditions for professional self-realization (Petrovsky A.V., Jaroshevsky M.G., 1990);

8. as an educational goal which consists in recognition, adoption, implementation by students of the criteria and norms relevant to the standard (Vaske J.M., 2001).

Thus, our understanding of critical thinking is close to the position that it is a mental activity based on the selection, analysis, evaluation, and implementation of new knowledge to make the right decisions and act on them.

Accordingly, professional critical thinking is believed to be an obligatory attribute of teacher professional competence and a resource of professional development by promoting positive values, life-long learning and personal social capabilities. Therefore, we suppose that professional critical thinking is a professionally oriented cognitive activity aimed at studying, modelling and transforming pedagogical environment accounted for by the purpose of teacher training, subject content and the experience of the participants of the education process. It is based on professional critical thinking strategies such as problem-solving, communication, creativity, open-mindedness revealing externally peculiarities of pedagogical reality, which are directed to preparing students for self-realization. Besides, built in the content of a teacher professional competence, professional critical thinking means that a person should have some special knowledge, professional critical thinking skills and dispositions, specific for teaching activity, which are manifested in the professionally oriented educational environment including subject content, professional situations, case studies, learning/teaching strategies which have a strong impact on students’ success. To sum up, professional critical thinking is a multifunctional cognitive activity integrated into teaching/learning process and contributing to the transformation of the quality of teacher professional competence to the higher level, thus forming an efficient and successful teacher.

As a pedagogical phenomenon, professional critical thinking contains in synthesis cognitive, procedural and personal components. The cognitive component includes metacognitive knowing (thinking that operates on declarative knowledge), metastrategic knowledge (thinking that operates on procedural knowledge) and epistemological knowing (encompassing how knowledge is produced) (Kuhn D., 1999). In addition, this component comprises motivation, which is a necessary condition for students to achieve their goals in learning their practice. The procedural component of professional critical thinking consists in a set of instructional skills which help students fulfill cognitive actions, appropriate to the thinking and modes of working that model the dispositions and working practices of education (Fielding M., 2004).

Moreover, professional critical thinking skills in combination with metacognition lead to the development of significant social and professional dispositions, which specify the habits of mind, and attitudes that enable a student to be a critical thinker (Siegel H., 1988). The personal component is apparent in the set of professional dispositions. There are three groups of such dispositions. The first group refers to the manner in which teachers treat students and includes respect for person, tolerance, etc., the second group is aimed at developing self-sufficiency and self-realization of students and includes the tasks of preparing students to be effective and successful, the third group is to initiate students into the rational traditions in the field of the professional activity and in becoming an active member of the society. The content of professional critical thinking is presented in Table 1.

Table 1

Structure of professional

critical thinking

Components |

Strategy/Definition/ Function |

Disposition |

Skill |

Cognitive |

1.Analysis The ability to carefully examine pedagogical reality

|

Intellectual responsibility, flexibility, taking into account the total situations, orderliness in working with complexity |

-asking thoughtful questions; -data analysis; -research; -interpretation; -judgement; -recognizing patterns; -skepticism. |

To examine, to understand, to explain, to implement |

|||

2.Creativity The ability to spot patterns, to formulate pedagogical problems

|

Mature and nuanced judgement, prudence on making judgement, abandoning non-productive strategies |

-diversity; -conceptualization; -curiosity; -imagination; -inferring; -vision. |

|

To select approach; to solve problems; to find out new ways, to define new ways of teaching. |

|||

Personal |

3.Open-mindedness To put aside any judgement about the peculiarities of pedagogical reality

|

Clarity on speaking, independent mindedness |

-diversity; -fairness; -humility; -inclusive; -objectivity; -observation; -reflection. |

To analyze information; to evaluate facts; to compare, to select |

|||

Instrumental

|

4.Communication The ability to build the contact between the participants of the educational process

|

Understanding of the opinions of other people, sociability, tolerance, generosity |

-active listening; -collaboration; -explanation; -interpersonal connection; -presentation; -team work; -verbal, written communication |

To come into contact, to work in a team, to figure out solutions, to solve problems

|

|||

5.Problem-solving To use generic methods in an orderly manner to find solutions to pedagogical problems

|

Anticipating possible consequences, seeking and offering reasons |

-attention to details; -clarification; -decision-making; -evaluation; -identification; -innovation. |

|

To analyze information; to evaluate facts; to compare, to select |

The second part of the investigation consists in studying teachers’ and students’ perception of professional critical thinking. 15 teachers and 60 students of South Ural State Humanitarian Pedagogical University (Chelyabinsk, Russia) participated in the survey.

The purpose of the survey was to identify the students’ and teachers’ perception of professional critical thinking and its role in the professional development of a teacher. 60 students were supposed to answer 6 questions. The results of the survey are presented in Table 2.

Table 2

A survey of students’ attitudes

to “critical thinking”

Question |

No |

Rather No than Yes |

Yes |

Rather Yes than No |

Difficult to answer |

1. Is in your opinion critical thinking a goal of teacher training process? |

48% |

27% |

1% |

18% |

6% |

2. Do you know what critical thinking means? |

15% |

27% |

21% |

17% |

20% |

3. Do you use critical thinking strategies in your study? |

31% |

16% |

18% |

23% |

12% |

4. Is critical thinking a priority for you in your study? |

82% |

9% |

0% |

2% |

7% |

5. Do you think critical thinking can make your future professional activity effective? |

18% |

10% |

35% |

29% |

8% |

6. Does studying at University contribute to the development of critical thinking? |

14% |

35% |

27% |

3% |

21% |

The findings of our study indicate that there is tension in the field related to the first question concerning a goal of teacher training process. In contrast to the scientific literature, the majority of respondents (about 75%) did not identify critical thinking as a goal of teacher training. The respondents believe that the aim of teacher training is a person development (both individually and socially). This position is quite relevant to the learner-centered approach supported by both Russian and foreign researchers as well. 19% of the surveyed consider critical thinking as a goal of teacher training and underline the influence of critical thinking on the quality of teacher professional competence.

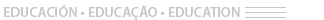

The positive answers of 38% of the responded to the second question allow us to divide them into three groups. The students belonging to the first group follow the narrow definition of this notion; they underline the leading role of the cognitive component. The students of the second group take into account a broader definition of critical thinking pointing to the cognition, skills and dispositions. As for the students of the third group, they combine critical thinking with reflection and criticality, which makes their answers vague. 41% of the surveyed notes that they use critical thinking strategies in their practice against 47% of the students who gives negative answers. 12% finds this question difficult to answer. It can be accounted for by the fact that these strategies are realized in teaching/learning process indirectly and students do not link their success in learning with them. The students were asked to name what critical thinking strategies mentioned in Тable 1 they use in their learning practice. The data received are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1

A survey of students' selected

strategies of critical thinking

91% of respondents indicates that professional critical thinking is not a priority for them, though 64% suggests that critical thinking can influences their future career. The absence of repetitive answers to the last question (49% against 58%) justifies that there is a great potential to improve a teacher training process.

On the top stage of the research, we asked 15 teachers about the place of critical thinking skills in their activity (Table 3).

Table 3

A survey of teachers’ attitudes to “critical thinking”

Question |

No |

Rather No than Yes |

Yes |

Rather Yes than No |

Difficult to answer |

1. Is in your opinion critical thinking a goal of teacher training process? |

21% |

12% |

41% |

26% |

0% |

2. Do you know what critical thinking means? |

12% |

13% |

59% |

15% |

1% |

3. Do you use critical thinking strategies in your work? |

12% |

19% |

29% |

36% |

4% |

4. Are critical thinking knowledge, skills and dispositions a priority for you in your work? |

11% |

13% |

31% |

35% |

10% |

5. Does critical thinking have a strong impact on your professional activity? |

3% |

8% |

70% |

19% |

0% |

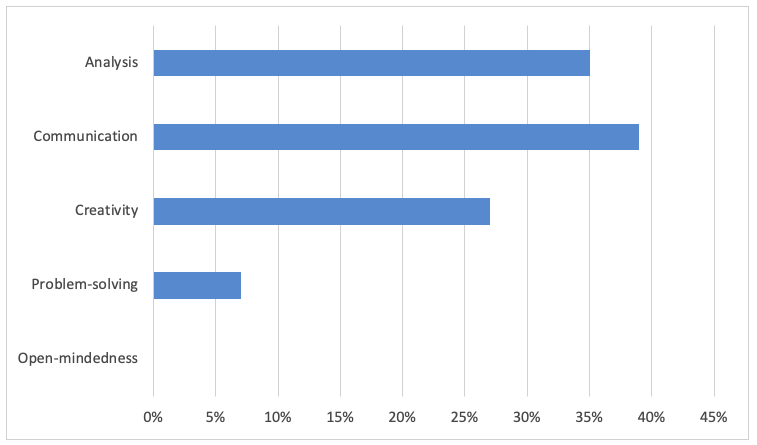

The majority of the teachers agree that critical thinking skills play a crucial role in their professional development (89%). Though 67% of the respondents agree that professional critical thinking is one of the goals of teacher training, only 66% admits that professional critical thinking is a priority for them and 10% is incapable to answer this question. 65% of the surveyed notes that they attempt to use these strategies indirectly through research work, subject content, project work etc. 31% of the surveyed answered negatively. They justify their option by the lack of time and the complexity of the subject content. Figure 2 shows what professional critical thinking strategies mentioned in Table 1 teachers use in their practice.

Figure 2

A survey of teachers' selected

strategies of critical thinking

The results presented in the research show that professional critical thinking has a significant focus on the development of teacher professional competence. The cognitive aspect of professional critical thinking can help to change orientation on the subject content while the procedural aspect, which includes a set of instrumental skills, is responsible for the promotion of different innovative learning and teaching technologies and strategies and contributes to the effective teaching/learning activities in which successful students integrate the functional and the personal. The cumulative effect of cognitive and procedural aspect leads to the formation of dispositions necessary for an effective and successful teacher.

The results of our study have brought us to the following conclusions:

1. Professional critical thinking is an indispensable requirement for the development of teacher professional competence, which enables a student to become efficient and successful. In this context, professional critical thinking can enhance and support more advanced teaching/learning processes.

2. Teaching and learning practices reveal that the development of critical thinking skills is mostly neglected in professional training since teachers and students lack information about critical thinking in general and professional critical thinking in particular, because most critical thinking effects are promoted indirectly, thus lessening the results of learning and reducing teaching efficiency.

3. We recommend that students should be provided with additional information about the nature and means of professional critical thinking.

4. The integration of scientific research and raising the level of students’ autonomy in educational process can facilitate the shift to creativity and reflexive technologies as a manifestation of professional critical thinking.

Brookfield, S.D. (1987). Developing critical thinking. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Dackenwald, G.G., Merriam, S.B. (1982). Adult education: Foundations of Practice. New York: Harper and Row.

Doyle, A. (2019). Critical thinking definition, skills and examples. http://www.thebalancecareers.com/criticalthinking-definition-authexamples-2063745.

Fielding, M. (2004). Effective Communication in Organisations. Publisher, Software Publications Pty, Limited.

Freire, P. (1989). Pedagogy of the oppressed (Rev. ed.). New York: Continuum.

Garrison, D.R. (1991). Critical thinking and adult education: A conceptual model for developing critical thinking in adult learners. International Journal of Life-long Education, 10 (4). 287-303 pp.

Gilmanshina, S. (2002). Professional thinking and features of its manifestation in the teacher activity. Structurally-functional and methodical aspects of activity of university complexes: materials of All-Russian Scientific-Methodical Conference. Kazan: Butlerov’s messages. 22-24 pp.

Hitchcock, D. (2018).Critical thinking. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

Kodekov, G. @etc. (2018). Model of developing professional thinking in modern education conditions. Opcion, Vol. 34. № 85-2. Venezuela: Universidad Del Zulia.

Kuhn, D. (1999). A Developmental Model of Critical Thinking https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X028002016.

McPeck, J.E (1990). Teaching critical thinking. London: Routledge.

Mezirow, J. (1991). Transformative dimensions of adult learning. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Jaroshevsky, M.G., Petrovsky, A.V., (1990). Dictionary of psychology. Moscow: Politisdat. 494pp.

Siegel, H. (1988). Education reason: Rationality, critical thinking, and education. New York: Routledge.

Thayer-Bacon, B.J. (2000). Transforming critical thinking: Thinking constructively. New York: Teacher College Press.

Vaske, J.M. (2001). Critical thinking in adult education. Critical Thinking in Adult Education: An Elusive Quest for a Definition of the Field. Ed. D. dissertation, Drake University.

1. South Ural State Humanitarian Pedagogical University. Foreign Languages Faculty. Professor. E-mail: afanasevaou@cspu.ru

2. South Ural State Medical University. Foreign Languages Department. Professor. E-mail: zinaidavozgova@mail.ru

3. South Ural State Humanitarian Pedagogical University. Foreign Languages Faculty. Associate Professor; South Ural State University. Foreign Languages Department. Associate Professor. E-mail: fedotovamv@cspu.ru

4. South Ural State Humanitarian Pedagogical University. Foreign Languages Faculty. Associate Professor. E-mail: msmirnova_737@mail.ru

[Index]

revistaespacios.com

This work is under a Creative Commons Attribution-

NonCommercial 4.0 International License