Vol. 40 (Number 39) Year 2019. Page 28

Vol. 40 (Number 39) Year 2019. Page 28

GOLUBEVA, Elena 1

Received: 20/07/2019 • Approved: 07/11/2019 • Published 11/11/2019

ABSTRACT: The article deals with the relevant problem of delayed parental family impact on the personal characteristics of an adult. One hundred thirty-eight young people, university students aged 18-23 years, were invited to participate in the study. The collected data were processed with the help of factor analysis (using the Statistica software package). The obtained results allow expanding the scientific understanding of the psychological consequences of adverse parent-child relationships and can be used by practicing psychologists in the work on actualizing psychological resource of young people. |

RESUMEN: El artículo aborda el problema relevante del impacto demorado de la familia parental en las características personales de un adulto. Ciento treinta y ocho jóvenes, estudiantes universitarios de 18 a 23 años, fueron invitados a participar en el estudio. Los datos recopilados se procesaron con la ayuda del análisis factorial (utilizando el paquete de software Statistica). Los resultados obtenidos permiten ampliar la comprensión científica de las consecuencias psicológicas de las relaciones adversas entre padres e hijos y pueden ser utilizados por psicólogos practicantes en el trabajo sobre la actualización del recurso psicológico de los jóvenes. |

The problem of family and how children perceived it has been essential in psychology for decades. Family and its impact on children were studied by M. Bowen (1978), D. Winnicott (1992), V. Satir and M. Baldwin (1983), etc.

A number of studies are concerned with child-parent relationships. R. Rohner and collegues developed Parental Acceptance-Rejection Theory, that aims to explain causes and consequences of parental rejection worldwide (Khaleque, 2002; Rohner, 2010; Rohner, Khaleque and Cournoyer, 2012; Rohner & Veneziano, 2001). D.R. Lopes, K. van Putten, and P.P. Moormann studied the impact of parental styles on the development of psychological complaints (Lopes, van Putten, and Moormann, 2015). E.V. Golubeva and O.N. Istratova studied experience of relations in the parental family as a predictor of psychological well-being in young Russians (Golubeva & Istratova, 2018a).

Summarizing the research results, parental love and warmth lead to the healthy development of a child’s personality, while parental cruelty or neglect disrupts a child’s development (Golubeva & Golubeva, 2018b). The problem is compounded in children from single-parent families (Golubeva & Golubeva, 2016) or orphan children (Golubeva & Golubeva, 2015).

The studies emphasize that it is not the relationships between the parent and the child that are important, but how the child perceives them. Their subjective perception may differ in one direction or another from the objective situation (revealed, for example, by an external observer or a researcher). Parental relationships continue to affect the child even in adulthood. In this situation, researchers use the term “perceptions of family relationships in childhood”.

There is scientific evidence that these perceptions affect an adult's psychological characteristics (Baeva, Kondakova, and Laktionova, 2018; Mallers, Charles, Neupert, and Almeida, 2010, etc). Within the personal characteristics, we analyze those that are most often included by scientists in the composition of psychological resource (coping strategies, psychological well-being, hardiness, reflection).

Psychological resources are such reserves, which enable people to cope with challenging or threatening events. It is also important to understand the correlations between psychological resources, which can “cooperate” with one another. There are several works devoted to revealing the links between the above-mentioned personal characteristics. In the Lazarus model, an event is considered stressful when a person appraises it as potentially dangerous to their psychological well-being.

Thus, researchers pay considerable attention to the relationships between coping strategies and psychological well-being. For instance, in research by E. Sagone and M. E. De Caroli, almost all dimensions of psychological well-being are negatively correlated with avoidance strategy and positively with problem solving coping. In addition, personal growth is positively correlated with reinterpretation (Sagone & De Caroli, 2014).

It was found that there is a negative relationship between hardiness and repressive coping (Maddi, Harvey, Knoshaba, Lu, Persico, and Brow, 2006). Negative and mixed effects from reflection on well-being were obtained (Lyke, 2009; Trapnell & Campbell, 1999).

Despite the recognition of the key role of childhood relationships with parents in personal development, there is not enough research devoted to their influence on the personal characteristics of an adult child, as well as on their correlation.

Therefore, the purpose of our study is to reveal correlation of personal characteristics in young people with different perceptions of their relationships with parents in childhood.

The sample consisted of 138 students (78 male and 60 female) of the Southern Federal University (Taganrog, Russia). The subjects ranged in age from 18 through 23 years (M=19.50, SD=1.57).

To study perceptions of childhood relationships with parents, the students were administered Biographisches Inventar zur Diagnose von Verhaltenstorungen (Jäger, 1976), which was standardized in Russia by V. A. Chiker (2006).

To study the personal characteristics, the students were administered:

- psychological well-being –the Ryff Scale of Psychological Well-being (Ryff & Keyes, 1995). The inventory was standardized in Russia by L. A. Pergamenshik (Pergamenshik, 2007);

- hardiness –the Personal Views Survey III-R (Maddi, 1997). The inventory was standardized in Russia by D. A. Leontyev and E. I. Rasskazova (2006);

- coping strategies – the Ways of Coping Questionnaire (Lazarus, 1993). The questionnaire was standardized in Russia by T. L. Krukova and E. V. Kuftyak (Krukova and Kuftyak 2007);

- reflection – the Reflection Questionnaire (Karpov, 2003).

The Biographical Inventory for the Diagnosis of Behavioral Disorders (BIV) aims at the diagnosis of behavioral problems in adults over the age of 18. It consists of 97 items, which are divided into eight subscales of ten to twenty items. Within a relatively short period of time, the BIV provides objective and standardized information about the biography, environmental situation and actual psychological state of the subject.

The “FAM” scale was used in the research, which provides a subjective description of the family situation in childhood and adolescence, as well as interactions with parents and other family relations.

High scores: unsatisfactory relationships with parents, inadequate family attitudes towards the outside world, negative influence of the family in childhood and adolescence.

Low scores: good interaction between parents, positive attitude of the family to the world, positive influence of the family in childhood and adolescence.

The Ryff Scale of Psychological Well-being is a psychometric inventory consisting of 84 items. Respondents rate statements on a scale from “1” to “6”, where “1” indicates strong disagreement and “6” – strong agreement. The Ryff Scale of Psychological Well-being is based on six factors: positive relations with others, autonomy, environmental mastery, personal growth, purpose in life, and self-acceptance. High total scores indicate a high level of psychological well-being.

The Personal Views Survey III-R is a questionnaire measuring the hardiness of one's beliefs about the interaction between the self and the world. The questionnaire scales are as follows: commitment, control and challenge. In the Russian variant, the questionnaire consists of 45 items.

The Ways of Coping questionnaire includes eight empirically constructed scales (confrontive, distancing, self-controlling, seeking social support, accepting responsibility, escape-avoidance, planful problem-solving and positive reappraisal).

The Reflection Questionnaire is designed to determine the level of reflexivity. The questionnaire scales include retrospective reflection (reflection on the past), situational reflection (reflection on the present), prospective reflection (reflection on the future) and reflection on communication. The questionnaire consists of 27 items.

Statistical analysis was implemented using the Statistica 6.0 software with the application of factor analysis. Factor analysis is a research technique designed to detect structure in the relationships between variables. Fifteen variables were used in the analysis: hardiness, psychological well-being, confrontive coping, distancing, self-controlling, seeking social support, accepting responsibility, escape-avoidance, planful problem solving, positive reappraisal, retrospective reflection, situational reflection, prospective reflection, reflection on communication, general reflection.

The principal components method was used. To obtain clear load patterns, the varimax typical rotational strategy was used.

The subjects were divided into two groups according to the BIV:

1. Favorable family situation (low FAM scores) – 92 subjects. Positive family relationship experience, contributing to the harmonious development of a child, positive perceptions of childhood relationships with parents. The FAM score is M = 2.52, SD = 1.63.

2. Unfavorable family situation (high FAM scores) – 46 subjects. Negative family relationship experience, contributing to the child's developmental distortion, negative perceptions of childhood relationships with parents. The FAM score is M = 8.61, SD = 1.86.

The results of the two groups of subjects were then analyzed separately in comparison with each other.

Young people with positive perceptions of childhood relationships with parents

Five factors were identified in the analysis. The eigenvalues for them were 4.07, 2.64, 2.25, 1.45, 1.06, which supports the choice of factors with eigenvalues above 1. The first five factors accounted for 76.45% of the variance (Table 1).

Table 1

Eigenvalues of factors (group 1)

Eigenvalue |

Total, % |

Cumulative Eigenvalue |

Cumulative, % |

|

1 |

4.07 |

27.11 |

4.07 |

27.11 |

2 |

2.64 |

17.62 |

6.71 |

44.73 |

3 |

2.25 |

14.98 |

8.96 |

59.71 |

4 |

1.45 |

9.67 |

10.41 |

69.38 |

5 |

1.06 |

7.07 |

11.47 |

76.45 |

Table 2 displays the matrix, which provides information about the loadings for each variable. The highest (value by module) loadings are marked in this table.

Table 2

Factor loadings (group 1)

Factor 1 |

Factor 2 |

Factor 3 |

Factor 4 |

Factor 5 |

|

Hardiness |

-0.03 |

-0.86 |

-0.09 |

0.04 |

-0.26 |

Psychological well-being |

-0.05 |

-0.91 |

-0.04 |

-0.15 |

-0.01 |

Confrontive coping |

-0.16 |

0.15 |

0.78 |

0.26 |

-0.01 |

Distancing |

-0.04 |

0.46 |

0.12 |

0.56 |

-0.02 |

Self-controlling |

0.10 |

-0.14 |

0.08 |

0.78 |

0.22 |

Seeking social support |

0.50 |

0.24 |

0.21 |

0.32 |

-0.33 |

Accepting responsibility |

0.02 |

0.54 |

0.58 |

0.14 |

-0.06 |

Escape-avoidance |

-0.10 |

0.50 |

0.08 |

0.71 |

-0.17 |

Planful problem solving |

0.30 |

-0.41 |

0.50 |

-0.33 |

0.25 |

Positiver |

0.17 |

0.03 |

0.79 |

-0.03 |

0.08 |

Retrospective reflection |

0.28 |

-0.02 |

0.15 |

0.24 |

0.76 |

Situational reflection |

0.73 |

-0.17 |

-0.15 |

0.04 |

0.27 |

Prospective reflection |

0.27 |

0.21 |

-0.02 |

-0.11 |

0.84 |

Reflection on communication |

0.89 |

0.03 |

0.10 |

-0.06 |

0.11 |

General reflection |

0.80 |

0.10 |

0.02 |

0.01 |

0.56 |

Expl. Var |

2.55 |

2.68 |

1.95 |

1.82 |

2.00 |

Prp. Totl |

0.17 |

0.18 |

0.13 |

0.12 |

0.13 |

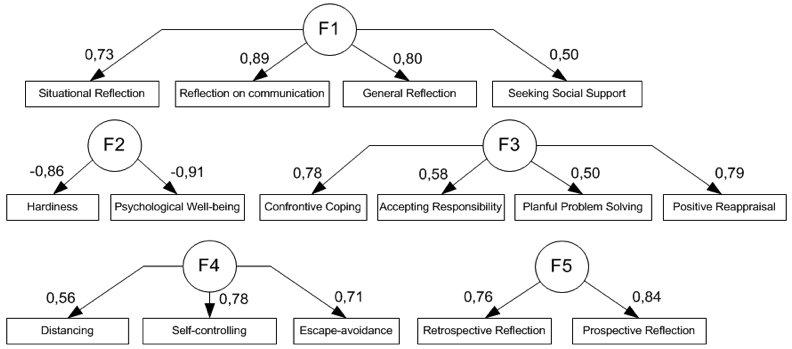

The findings presented in Table 2 indicate that the first factor has the most important contribution from reflection on communication and includes general reflection, situational reflection, and seeking social support.

The second factor includes two variables – hardiness and psychological well-being.

The third factor includes the following coping strategies: positive reappraisal, confrontive coping, accepting responsibility, and planful problem solving.

The fourth factor includes coping strategies of different types: self-controlling, escape-avoidance and distancing.

The fifth factor includes prospective and retrospective reflection.

All factors in this factor structure are unipolar. This means that correction between variables is positive in all cases.

The findings obtained during the conducted factor analysis are also provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Factor structure of personal characteristics in young people with

positive perceptions of childhood relationships with parents.

Young people with negative perceptions of childhood relationships with parents

Five factors were identified as a result of the analysis, just like in the previous calculations. The eigenvalues for them were 3.68, 3.34, 1.65, 1.29, 1.05, which supports the choice of factors with eigenvalues above 1. The first five factors accounted for 73.43% of the variance (Table 3).

Table 3

Eigenvalues of factors (group 2)

Eigenvalue |

Total, % |

Cumulative Eigenvalue |

Cumulative, % |

|

1 |

3.68 |

24.56 |

3.68 |

24.56 |

2 |

3.34 |

22.27 |

7.02 |

46.83 |

3 |

1.65 |

10.98 |

8.67 |

57.82 |

4 |

1.29 |

8.60 |

9.96 |

66.41 |

5 |

1.05 |

7.02 |

11.01 |

73.43 |

Table 4 displays the matrix, which provides information about the loadings for each variable. The highest (value by module) loadings are marked in this table.

Table 4

Factor loadings (group 2)

|

Factor 1 |

Factor 2 |

Factor 3 |

Factor 4 |

Factor 5 |

Hardiness |

-0.26 |

0.81 |

-0.13 |

-0.08 |

-0.17 |

Psychological well-being |

0.05 |

0.86 |

-0.07 |

0.25 |

-0.08 |

Confrontive coping |

0.51 |

0.47 |

0.35 |

0.09 |

-0.07 |

Distancing |

0.80 |

-0.06 |

-0.01 |

0.19 |

0.08 |

Self-controlling |

0.05 |

0.01 |

0.15 |

0.89 |

0.06 |

Seeking social support |

0.69 |

0.18 |

-0.09 |

0.07 |

0.04 |

Accepting responsibility |

0.76 |

-0.11 |

0.33 |

0.09 |

0.00 |

Escape-avoidance |

0.79 |

-0.15 |

0.02 |

-0.09 |

0.45 |

Planful problem solving |

-0.16 |

0.40 |

0.11 |

0.40 |

-0.60 |

Positive reappraisal |

0.12 |

0.18 |

-0.18 |

0.86 |

0.02 |

Retrospective reflection |

0.17 |

-0.21 |

0.33 |

0.28 |

0.77 |

Situational reflection |

0.15 |

0.50 |

0.38 |

0.00 |

0.56 |

Prospective reflection |

-0.18 |

0.04 |

0.90 |

0.09 |

0.04 |

Reflection on communication |

0.19 |

-0.17 |

0.81 |

-0.09 |

-0.08 |

General reflection |

0.20 |

0.00 |

0.91 |

-0.02 |

0.32 |

Expl. Var |

2.86 |

2.20 |

2.88 |

1.90 |

1.63 |

Prp. Totl |

0.19 |

0.15 |

0.19 |

0.13 |

0.11 |

The first factor includes coping strategies of different types: distancing, escape-avoidance, accepting responsibility, seeking social support, confrontive coping.

The second factor includes hardiness and psychological well-being.

The third factor includes various types of reflection: general reflection, prospective reflection and reflection on communication.

The fourth factor contains the following coping strategies: self-controling and positive reappraisal.

The fifth factor includes retrospective reflection, planful problem solving and situational reflection. The fifth factor is the only bipolar factor in this factor structure. This means that the correlation between some variables is negative.

The findings obtained during the conducted factor analysis are provided in Figure 2.

Figure 2

Factor structure of personal characteristics in young people

with negative perceptions of childhood relationships with parents

Comparison of the factor structures of personal characteristics of young people with different perceptions of childhood relationships with parents shows the following results.

In both factor structures, hardiness and well-being are united in one factor and have the same signs. This indicates that these personal characteristics are closely related regardless of family perceptions. Detection of the link between hardiness and well-being corresponds with psychological research in this field (Rizvi, 2016).

It was expected that hardiness would be negative with repressing coping. It is known that repressors scored lower on escape-avoidance and higher on planful problem solving than nonrepressors (Parker & McNally, 2008). Although these coping strategies are not included in the factor, to which hardiness belongs, in most cases, they have high loadings with it with an appropriate sign (for young people with positive perceptions of their relationships with parents: hardiness = -0.86, escape-avoidance = 0.5, planful problem solving = -0.41; for young people with negative perceptions of their relationships with parents: hardiness = 0.81, escape-avoidance = -0.15, planful problem solving = 0.40).

Thus, the detection of these connections can be considered predictable. It confirms earlier psychological studies and does not dependent on the perception of relationships with parents in childhood.

Next, we consider the differences between the factor structures of young people with different perceptions of their relationships with parents in childhood.

The factor structure of young people with positive perceptions includes F1, which consists of reflection on the present, reflection on communication, general reflection, and one of the coping strategies – seeking for social support. The presence of such a link (all loadings with the same signs) indicates that the key resource of this group is understanding oneself in the present, as well as one’s relationships with others, who are the source of support. It seems that the positive experience of relationships in the parental family actualizes this resource.

F3 and F4 combine coping strategies, with F3 including “active” strategies (confrontive coping, accepting responsibility, planful problem solving, positive reappraisal) and F4 includes “passive” strategies (distancing, self-controlling, escape-avoidance). Thus, the coping strategies of young people in this group are clearly differentiated.

F5 includes reflection on the past and the future. Their combination in one factor can mean the continuity and integrity of the life path of young people, the lack of desire to ignore the past, in which the experience of relationships with parents in childhood plays a serious role.

The factor structure of young people with negative perceptions includes F1, which contains combined coping strategies, both “active” (confrontive coping, seeking social support, accepting responsibility) and “passive” (distancing, escape-avoidance). F1 and F4 combine an undifferentiated set of coping strategies, which becomes the key resource for young people in this group.

F3 includes reflection on the future, reflection on communication, and general reflection. It is noteworthy that reflection on communication turned out to be associated with reflection on the future. Perhaps dissatisfaction with the current communication situation makes young people consider it in the context of future changes. This may be due to the negative experience of relationships in the parental family.

F5 is a combination of planful problem solving, reflection on the past and reflection on the present and it is bipolar. This means that neither reflection on the past nor reflection on the present "help" in solving problems. That is, the gained experience, part of which is the experience of relationships in the parental family, does not contain situations of achieving success in various spheres of life.

The differences in the factor structure of personal characteristics among young people with different perceptions of their relationships with parents in childhood were detected.

In individuals with positive perceptions, reflection is positively associated with the search for social support. Self-awareness in these young people is closely connected with a reliance on loved ones, which may be due to the positive experience of relationships in the parental family.

In individuals with negative perceptions, reflection is negatively associated with problem-solving planning. The awareness of oneself (one's past and present) of these young people impedes overcoming difficulties due to, possibly, the negative experience of relationships in the parental family.

The obtained results allow expanding the scientific understanding of the psychological consequences of adverse parent-child relationships and can be used by practicing psychologists in the work on actualizing psychological resource of young people.

The research was financially supported by the Southern Federal University.

Baeva, I. A., Kondakova, I. V., and Laktionova, E.B. (2018). Psychological resources of adults who experienced violence in childhood. The European Proceedings of Social & Behavioural Sciences. Retrieved from https://dx.doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2018.11.02.10

Bowen, M. (1978). Family Therapy in Clinical Practice. New York: Jason Aronson.

Chiker, V. A. (2006). Psikhologicheskaya diagnostika organizatsii i personala [Psychological diagnostics of organization and personnel]. Saint-Petersburg: Rech, 176 p.

Golubeva E. V., and Golubeva I. V. (2015). Deformations in economic consciousness of children raised in orphanages. SAGE Open, 5(3). Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244015604191

Golubeva, E. V., and Golubeva, I. V. (2016). Child’s vision of family. The Social Sciences, 11(25), 6781-6788. DOI: 10.3923/sscience.2016.6781.6788.

Golubeva, E. V., and Istratova, O. N. (2018a). Experience of relations in the parental family as a predictor of psychological well-being in young people. Azimuth of Scientific Research: Pedagogy and Psychology, 7, 2(23) 358-362.

Golubeva, E. V., and Istratova, O. N. (2018b). Study of Frustration in Children Emotionally Rejected by Their Parents. Espacios, 39(52), p.2. Retrieved from http://www.revistaespacios.com/a18v39n52/18395202.html

Jäger, R.S. (1976). Biographical Inventory for the Diagnosis of Behavioral Disorders, BIV: Hand Instructions by Reinhold Jäger. Göttingen [ua]: Hogrefe, 55 p.

Khaleque, A. (2002). Parental love and human development: implications of parental acceptance-rejection theory. Pakistan Journal of Psychological Research, 17 (3-4), 111-122.

Karpov, A. A. (2003). Refleksivnost kak psichicheskoye svoystvo i metodika eyo diagnostiki [Reflexivity as a psychic property and techniques of its diagnosis]. Psychological journal, 24(5), 45-57.

Krukova, T. L. and Kuftyak, E. V. (2007). Sposobi sovladayuschego povedeniya (Adaptatsiya WCQ) [Ways of coping strategies (WCQ adaptation)]. Journal of practicing psychologist, 3, 93-112.

Lazarus, R. (1993). Coping Theory and Research: Past, Present, and Future. Psychosomatic Medicine, 55, 234-247.

Leontyev, D. A., and Rasskazova, E. I. (2006). Test zhiznestoykosti [Hardiness Inventory]. Moscow: Smisl, 63 p.

Lopes, D. R., van Putten, K., and Moormann, P. P. (2015). The impact of parental styles on the development of psychological complaints. Europe's Journal of Psychology, 11(1), 155-168.

Lyke, J. A. (2009). Insight, but not self-reflection, is related to subjective well-being. Personality and Individual Differences, 46, 66–70. DOI:10.1016/j.paid.2008.09.010.

Mallers, M. H., Charles, S. T., Neupert, S. D., and Almeida, D.M. (2010). Perceptions of childhood relationships with mother and father: daily emotional and stressor experiences in adulthood. Dev Psychol., 46(6), 1651–1661. DOI:10.1037/a0021020.

Maddi, S. R. (1997). Personal views survey II: A measure of dispositional hardiness. In C. P. Zalaquett & R. J. Wood (Eds.), Evaluating stress: A book of resources. Lanham, Md.: Scarecrow Press, Inc.

Maddi, S. R., Harvey, R. H., Khoshaba, D. M., Lu, J. L., Persico, M., and Brow, M. (2006). The personality construct of hardiness, III: Relationships with repression, innovativeness, authoritarianism, and performance. Journal of Personality, 74(2), 575–597.

Parker, H. A., and McNally, R. J. (2008). Repressive Coping, Emotional Adjustment, and Cognition in People Who Have Lost Loved Ones to Suicide. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 38(6), pp. 676-687.

Pergamenshik, L. A. (2007). Skali psihologicheskogo blagopoluchiya Ryff: protsess i rezultati adaptatsii [Ryff Scales of Psychological Well-Being: adaptation procedure and results]. Psychological diagnostics, 3, 73-96.

Rizvi, T. (2016). A study of relationship between hardiness and psychological well-being in university students. International Journal of Advanced Research, 4(11), 2340-2343. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.21474/IJAR01/2344

Rohner, R. P. (2010). Perceived teacher acceptance, parental acceptance, and the adjustment, achievement, and behavior of school-going youth internationally. Cross-Cultural Research, 44(3), 211-221.

Rohner, R. P., Khaleque, A., and Cournoyer, D. E. (2012). Introduction to parental acceptance-rejection theory, methods, evidence, and implications. University of Connecticut. Retrieved from www.csiar.uconn.edu

Rohner, R. P., and Veneziano, R. A. (2001). The importance of father love: History and contemporary evidence. Review of General Psychology, 5, 382-405.

Ryff, C., and Keyes, C. (1995). The structure of psychological well-being revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69, 719–727.

Sagone, E., and De Caroli, M. E. (2014). A Correlational Study on Dispositional Resilience, Psychological Well-being, and Coping Strategies in University Students. American Journal of Educational Research, 2(7), 463-471.

Satir, V., and Baldwin, M. (1983). Satir step by step: a guide to creating change in families. Palo Alto, CA: Science and Behavior Books.

Trapnell, P. D., and Campbell, D. T. (1999). Private self-consciousness and the five-factor model of personality: Distinguishing rumination from reflection. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76, 284–304. DOI:10.1037/0022–3514.76.2.284.

Winnicott, D. W. (1992). The Family and Individual Development. London: Routledge.

1. Southern Federal University, 105/42, Bolshaya Sadovaya Str., Rostov-on-Don, 344006, Russia