Vol. 40 (Number 24) Year 2019. Page 17

AHMED, Adel 1 & ELKHATIB, Sobhy 2

Received: 29/03/2019 • Approved: 24/06/2019 • Published 15/07/2019

ABSTRACT: Information and communications technology (ICT) in supply chain management has enabled corporations to use offshore facilities for outsourcing commercial activities. This has expanded service trade significantly but poses challenges for tax authorities. This article deals with one of the important issues – the supply chain management in E-commerce and taxation industries and the Permanent Establishment rule which mean is any fixed place of business of the employer and includes a branch, a mine, an oil well, a gas well, a farm, timberland, a factory, a workshop, a warehouse, an office and an agency. This article examines issues surrounding the (1) rapid expansion of global electronic commerce in the context of supply chain management, (2) extant theory of taxation, (3) policy considerations and (4) e-commerce in the context of taxation. Based on the examples, this article explores the effective methods of supply chain management in the E-commerce industry, creates a taxonomy of recommender systems, including the interfaces they present to customers, the technologies used to create the recommendations, and the inputs they need from customers. |

RESUMO: A tecnologia de informação e comunicação (TIC) na gestão da cadeia de suprimentos permitiu que as corporações usassem instalações offshore para terceirizar atividades comerciais. Isso ampliou significativamente o comércio de serviços, mas apresenta desafios para as autoridades fiscais. Este documento tratará de uma das questões importantes - a gestão da cadeia de suprimentos nas indústrias de comércio eletrônico e tributação e a regra do Estabelecimento Permanente que significa qualquer local fixo de negócios do empregador e inclui uma filial, uma mina, um poço de petróleo, um poço de gás, uma fazenda, uma fábrica, uma oficina, um armazém, um escritório e uma agência. Este artigo examina questões que envolvem a (1) rápida expansão do comércio eletrônico global no contexto da gestão da cadeia de suprimentos, (2) a teoria da tributação existente, (3) considerações de política e (4) e-commerce no contexto da tributação. Com base nos exemplos, este artigo explora os métodos eficazes de gerenciamento da cadeia de suprimentos na indústria de comércio eletrônico, cria uma taxonomia de sistemas de recomendação, incluindo as interfaces que eles apresentam aos clientes, as tecnologias usadas para criar as recomendações e as entradas necessárias dos clientes. |

E-Commerce logistic in Supply chain management (LSCM) is doing business over the Internet.

In the E-commerce LSCM, there are two major types of business models: business to consumer (B2C) and business to business (B2B). It also includes the subscription to and use of an internet service provider (ISP) or an online service provider (OSP), and has also been held to cover electronic data interchange (EDI), electronic fund transfers (EFT) and all credit and debit card activity. In B2C model, business website is a place where all the transactions take place between a business organization and consumer directly (Mangiaracina et al., 2015). In this model, a consumer visits the website and places an order to buy the products. The main supporting Techniques for E-commerce logistics include E-commerce system, warehouse management system (WMS), and transportation management system (TMS). For a typical company which is able to carry out E-commerce business, an online system or platform is necessary (Yu et al., 2017). Services play a crucial role in supply chain systems. There are a number of studies that review and discuss different definitions of service supply chain systems and service supply chain management (Sawik, 2014). In a supply chain system, by definition, there must be a “product” that is created by “the points of origin” and delivered at “the points of consumption”. This “product” can be a tangible physical product or a service product. In the domain of service supply chain management, two types of supply chain systems arise, namely the Service Only Supply Chains (SOSCs) and the Product Service Supply Chains (PSSCs) (Wang et al., 2015 ).

Definitions for E-Commerce vary considerably. However, consideration of two brief definitions raises some basic issues. Thus it has been said that: Electronic commerce in SCM is a broad concept that covers any commercial transaction that is effected via electronic means and would include such means as facsimile, telex, EDI, Internet and telephone. For the purposes of this paper the term is limited to those trade and commercial transactions involving computer-to-computer communications whether utilising an open or closed network. (Attorney, 1998). In addition, it has also been said that: electronic commerce in SCM could be said to comprise commercial transactions, whether between private individuals or commercial entities, which take place in or over electronic networks. The matters dealt with in the transactions could be intangibles, data products or tangible goods. The only important factor is that the communication transactions take place over an electronic medium (Davies, 1998). These definitions raise issues in relation to the form of communication, the subject matter of the transactions and the contracting parties. The first of the above definitions emphasises that e-commerce in SCM, in broad sense, could encompass trading carried out by means of communication that can be labelled ‘electronic’. However, it emphasises computer-to-computer transactions and the concern here is basically email and web-based communication, which are sufficiently different from the more traditional means of communication to raise significant issues for the law. The second definition includes some recognition of the different types of subject matter of electronic contracts. Such contracts may simply be concerned with traditional goods or services to be delivered in the traditional way. However e-commerce does not simply provide a new means of making contracts. In some situations it also provides a new method of performance. (Rowland and Elizabeth, 2000). The main object of the concept of the definition of a permanent establishment in a double tax agreement is to set out the type and permanency of business activities that an entity must conduct before they can be subject to tax in another jurisdiction. Furthermore, the definition of a 'permanent establishment' as defined in article 5 of the OECD model tax convention requires the existence of a fixed place of business. This indicates the existence of a facility with a certain degree of permanence. The internet has changed the traditional international business model. It is no longer necessary that the entrepreneur, or his employees, agents, branches or intermediaries is in the country where the business is being conducted. It is clear that the internet overcomes the traditional limitations of physical presence in a jurisdiction when doing business. This poses a challenge when it comes to the determination of a 'permanent establishment', as the test is based on a physical presence of an entity in a jurisdiction. Taking into account that e-commerce in SCM was not a factor when the basis of the definition of the definition of a permanent establishment was formulated. There is no international organization governing international corporate taxation. To address this problem of global governance, the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) have initiated an International Dialogue on Taxation to lend policy coherence at the global level (www.itdweb.org/documents/BG3.html ). The international taxation of business profits has received some attention among economists and tax experts, but academic of accounting and tax have shown little engagement with this issue area.

It is now accepted that the Internet may facilitate a strategy of competing internationally. This paper discusses the taxation implications of following such a strategy. A key question is whether existing tax systems can cope with a trading mechanism which is perceived as achieving something very new, or whether different models are needed. The Internet is creating a unique global marketplace that has the potential to change profoundly the way international business is conceptualised and configured (Bennett, 1997; Srirojanant & Thirkell, 1999; Kedia & Harveston, 1999). The rapid commercialization of the Internet calls into question many of the fundamental tenets of international business (Hamill & Gregory, 1997). Issues such as the barriers to internationalisation faced by small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs); incremental, evolutionary internationalisation; the importance of overseas agents and distributors to export success; country screening; market concentration versus market spreading, etc., take on a new perspective. The use of the Internet for global marketing ‘enables firms to leap-frog the conventional stages of internationalisation, as it removes all geographical constraints, permits the instant establishment of virtual branches throughout the world, and allows direct and immediate foreign market entry to the smallest of businesses’ (Bennett, 1997). Kedia and Harveston (1999) recall that the domain of international business has typically been dominated by large firms that have internationalized either incrementally or by progressing through a sequence of identifiable stages. Previous research has indicated that firms go through a process of evolutionary development in terms of depth of operational mode and product offerings (goods, know-how, services and systems). Probably the best-known model of the internationalisation process is that of the Uppsala school (Johanson & Wiedersheim-Paul, 1975; Johanson & Vahlne, 1977, 1990). This model describes a sequential progression from export through knowledge agreements, such as licensing or franchising, to foreign direct investment. These firms have been referred to as gradual globalisers. In contrast, a number of new ventures has recently appeared with a significant amount of international activities from inception (Oviatt & McDougall, 1995; Cavusgil & Knight, 1997). These organisations have been referred to as ‘born global’ firms. There is a clear sense in which Internet-based strategies permit SMEs to be born global. Hamill and Gregory (1997) consider it is a legitimate question to ask whether the slow, evolutionary stages of development approach to internationalisation remains valid when Internet technology and the WWW provide SMEs with a lowcost ‘gateway’ to global markets. In terms of taxation, the impact of this development and the speed at which it has occurred is significant. In the past, national revenue jurisdictions had time to react to slowly occurring changes and implement taxation policies and statutes to deal with them in a timely manner. Often any jurisdiction had only to consider its own needs. In a time of fast-developing technical changes, a revenue authority lags behind. It takes considerable time to formulate policy and establish it within a legal framework. By the time this has been done, the new law could have been overtaken by further innovations, which could require yet further statute to address their taxation implications. Moreover, e-commerce in SCM by nature is multi-jurisdictional, so a national taxing authority must necessarily consider its interfaces with other jurisdictions more prominently than before. Electronic commerce in LSCM is an opportunity for traders (though not without its problems) : for tax authorities it is a potential menace, because: (Sweetman, 2003)

The rest of the paper is organised as follows. The following section examines the rapid of global electronic commerce in SCM, tax principles relevant to e-commerce taxation. The third section examines reasons for considering e-commerce in SCM as conceptually the same as trade by other means, together with current world-wide experiences. The fourth section looks at the concept of Permanent Establishment. Conclusions are in the final section.

This article will address the challenges and prospects the global electronic commerce in SCM, studying theory of taxation. Taxation theory as applied today derives from the four canons of taxation developed by Adam Smith in 1776 in “An Enquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations”. In addition to certainty, convenience and efficiency, equity was fundamental. Afterward, theorists have added neutrality, simplicity and flexibility. Equity in its basic meaning of fairness has two aspects. The first is that subjects of a State (which at present include companies, as these are legal entities) that contribute to the support of government as nearly as possible in proportion to the revenue they respectively enjoy under the protection of the State. Secondly, the individual circumstances of the person should be considered.

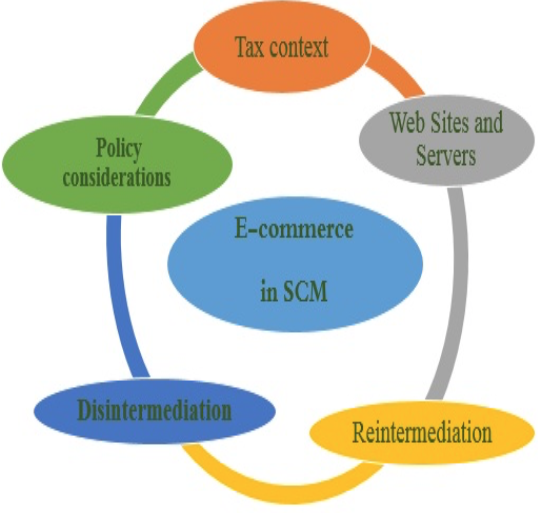

Additionally examine the main factors of e-commerce (Fig.1)

Figure 1

Components of e-commerce in SCM

Perfect competition in today’s global markets and the International heightened expectations of customers bounded business enterprises to explore the factors affecting supply chain performance. Though from the economic perspective that e-business/e-commerce has become one of the fastest growing sectors, the globalization and technology has brought the operations of supply chain into a new era and the consensus customers’ acceptance of online shopping is not concluded. Additionally, the pace of technology development is so fast that it is possible every half a year there might be something new appears and available in the market. Therefore, it is difficult to anticipate how the e-business/e-commerce as the most favour of the global supply chain model will trend. The authors aim to hold a critical position to understand how globalization and technology as two key drivers impact the e-business/e-commerce.

Electronic commerce in SCM comprises the electronic sale by online stores of downloadable ‘soft merchandise’ such as music, e-books, e-newsletters, photos and video recordings, software and documents (direct e-commerce), the electronic ordering of tangible products (indirect e-commerce), online securities transactions as well as the provision of financial or other services.

The fundamental characteristic of e-commerce in SCM, which distinguishes it from traditional commercial activity, is that it is conducted by electronic means. Thus, the marketing of products or services is carried out through the enterprise’s web site; customers browse online catalogues and use secure online-shopping cart systems; orders are made via interactive online order forms; payment is effected by credit card via secure payment systems; and delivery is either arranged by traditional means (mail, shipment, etc.) or alternatively by allowing the downloading of digitalised products from the web site onto the consumer’s computer.

E-commerce in SCM is characterised by the following features. It is: (Chetcuti, 2003)

• Potentially virtual – the presence of an enterprise in another country may be wholly based on the hosting of a web-site on a server located there.

• Disintermediated and less labour intensive – the main enterprise no longer requires intermediaries in foreign countries to be able to conduct business there. Moreover, e-business activities require far less human intervention, if any, than that otherwise required to trade by in a traditional manner.

• Global – the scope of market-penetration is unlimited and knows no borders;

• Anonymous – business is transacted on a non-face to face basis and therefore the seller and the consumer may not know each other.

The idea of vertical equity suggests that persons in different circumstances should be treated differently. For example, high wage earners should pay more tax than low wage earners (whether by proportional or progressive taxes). Horizontal equity on the other hand suggests that persons in similar circumstances should be treated similarly. A person who has acquired £35,000 is the same as another with the same amount of money, therefore they should be treated similarly. However, the vertical equity concept would suggest that treatment might need to be different if one person had £35,000 as earned income and the other as capital profits arising on the disposal of assets. There are differences even in the notion of ‘person’, which make a distinction in this context.

Corporations/companies arrived later as business entities than sole traders or partnerships. In the UK, for instance, no tax distinction was drawn between unincorporated and incorporated businesses, when the latter became increasingly used as means of doing business: both paid income tax (though companies had no personal reliefs and allowances and were not liable at graduated rates). Not until 1965 was there, in fact, a separate tax on company profits, although there had been some temporary forerunners in the form of excess profits taxes and national defence contributions levied on companies (Nightingale, 2000). The tax introduced in 1965 did not differentiate between distributed and retained profits, thus dividends were doubly taxed until the partial imputation system was introduced in 1973. Although both individuals and companies could make profits from being in business, it was the way in which companies rewarded their providers of capital from those business profits which helped bring about a fundamental difference in the way those profits are now both perceived and taxed. The point here is that an attempt to treat both in the same way for taxation purposes ultimately foundered not because the two entities were doing anything inherently different, but they had a different formal structure at law which dictated what could be done with profits. In terms of e-commerce, the basic research question which needs to be asked is whether the form of doing business over the Internet is in itself different or brings about new outcomes or procedures, which require new or different tax policies or treatments. Sometimes differences are not immediately apparent: the case of taxation of company profits cited above underlines this. At present a great deal is being written about taxation and e-commerce from a practitioner or country standpoint. The debate basically hinges on whether e-commerce transactions can be fitted into existing national tax frameworks – with clarification on certain issues or extending definitions as and when required.

One of the first steps in any international financial structuring is to determine whether a PE exists. According to the OECD, a PE is simply a fixed place of business, through which the business of an enterprise is wholly or partly carried on. Traditionally under the OECD Model one of two test must be met to determine whether a PE exists: the Physical Presence Test or the Agency Presence Test. The Physical Presence Test establishing a PE can be met if a fixed place of business is established or the activity is listed in Article 5. Examples include: a branch, an office or a workshop. A building site or construction project is also considered a PE if it lasts more than 12 months. Section 4(f) of Article 5 also sets out specifically enumerated activities which are not PEs. These include: use of facilities solely for the purpose of storage, display or delivery of goods or maintenance of a fixed place of business solely for the purpose of purchasing goods or for collecting information for the foreign company. By applying this language of Article 5 Section 4(f) to a typical e-commerce situation, it is clear that this description covers a web site, and the activities of a server. Furthermore, it seems that since a web site has no physical presence, it cannot be a PE. However, it is debatable whether a server is a PE in the true sense of the word.

The Agency Presence Test looks at whether a person or company is acting on behalf of the foreign enterprise with the authority to conclude contracts in that entity's name and does so repeatedly. If the server company is deemed to be an agent, it must be a dependent agent, otherwise it may not satisfy the requirements of being a PE. Dependent agency, according to the OECD commentary, is considered to exist if the agent's commercial activities for the enterprise are subject to detailed instructions or to comprehensive control by the principal. In other words: is the agent organizationally bound both legally and economically by the directions of the principal?

In contrast to a dependent agent, an independent agent is one who is both legally and economically independent and acts within the ordinary course of its business. This is measured by looking at the normal business activities of the particular trade to which the agent belongs. An independent agent can still be deemed to be a PE if it acts outside its ordinary course of business. With regard to e-commerce, one must determine whether an independent internet service provider (ISP) is acting outside its ordinary course of business activities for ISP companies by providing a platform where web sites can be accessed. Clearly, an ISP's trade is almost always to provide clients with the ability to base web pages on their server. Therefore, if the ISP is acting within the normal scope of its business activities and if it is not organizationally bound by the principal, then it would most probably be deemed an independent agent acting within its ordinary course of business and not a PE.

The tax treatment of cross-border commerce is the subject of bilateral tax treaties which are often negotiated versions of the OECD Model Tax Convention. According to Article 7 of OECD Model, the source country may tax the profits arising from commercial activity carried out within its borders by a foreign entity through a substantial physical presence in the source country. To justify source taxation, such presence must reach the level of a ‘permanent establishment’ by satisfying the following three prerequisites, namely that there must be a distinct place, such as premises, or in certain instances, machinery or equipment (“place-of-business test”), that this must be established with a certain degree of permanence (“permanence test”), and that business must be carried on through the place, usually by personnel of the enterprise (“business-activities test”). If the presence does not reach the level required by the OECD Model by satisfying these requirements, the source state is not entitled to charge income tax on the profits arising from the international transaction; rather, the residence country will have the right to tax the profits of its resident.

The requirement of a PE in source countries is comparable to the US substantial physical presence test. Constitutionally, in the US, a state is entitled to impose state and local sales taxes an enterprise of another US state only if such business maintains a substantial physical presence within the former state.

Historically, the concept of PE answered the internationally-felt need for a quantitative criterion for ascertaining the taxability or otherwise of foreign commercial activity in the source state. The PE principle provided sufficient evidence that a foreign company’s business within the source country was substantial enough to justify the imposition of fiscal compliance burdens on the foreign company in that country.

This concept satisfied the requirement of certainty and predictability of tax law in that it provided multinational companies with relatively clear rules to determine in advance whether and in what way their activities abroad would be taxed by foreign tax authorities. Furthermore, the PE principle presented states with an internationally equitable rule for sharing the benefits of cross-border commerce – source country taxation rewards importing countries for opening to foreign businesses the commercial opportunities available within their markets, while net-exporting countries obviously reap the benefits of taxing value added at the production stage.

With the advent of the Digital Age, the international tax community saw the PE concept face its first major challenge. With the dotcom boom at its peak, e-tailing ventures selling digitalised products appeared, tapping into the global online market and capitalising on the lower overheads associated with on-line trading.

Traditionally, multinational corporations have sought to penetrate foreign markets by setting up physical intermediaries within the targeted markets. For instance, retailers have carried out their marketing campaigns via sales offices operating in the foreign market. These physical intermediaries often constituted PEs under tax treaties, triggering source-based taxation.

The picture changes with the availability of e-commerce in SCM opportunities. E-tailers such as Amazon.com effect the greater part of their market research, advertising, marketing and sales through a web site. This increases competitiveness, transferring transaction costs, including product selection, to customers so that the cost-savings for the online retailer is tremendous. Thus, the Internet can be seen as an “agent of disintermediation” because it removes the necessity for certain intermediaries. Even stockbrokers have felt the pinch of online competition. E-trade.com permits retail stock trading without brokers, along with Charles Schwab, Datek Online, CyberInvest.com, Ameritrade, Inc., 5Paisa.com and a multitude of other e-brokers now in the trade.

For the multinational corporation, disintermediation means shifting part of their business operations from their physical intermediaries in source countries to their e-commerce base in the country of residence, thereby centralising their administrative, sales, marketing and after-sales operations and outsource non-essential functions to foreign affiliates. For source countries, this means a loss of source-generated taxable profits and, as long as international tax rules insist on the physical presence requirement, their tax base will suffer further erosion.

The latest internet technologies can now also perform those tasks traditionally carried out in source countries by dependent agents or employees employed by multinationals. Complex contracts can be concluded remotely and new business relationships created online. The processes of order collection, contract negotiation and payment collection can now be automated. The removal of dependent agents habitually concluding contracts in the source state means that a PE may no longer be present under most tax treaties. The same result can be achieved by replacing dependent agents with independent agents acting on instructions to perform the same tasks. Meanwhile, customer relationships are maintained via the company’s intranet. Under the current international tax regime, no tax can be chargeable by the source state for the corporation’s activities in its market.

New opportunities are created especially in the B2B sector for the role of the ‘cybermediary’, an online company engaged in facilitating business transactions online, without having fixed places of business within source countries. Online “infomediaries”, like Vertacross.com and Ariba.com operating in the e-procurement business bring buyers and sellers together on the Internet, greatly reducing transaction costs for both parties. These new intermediaries are performing operations outsourced to them by multinational corporations.

With more and more businesses going virtual and with a greater portion of source state activity carried out without a PE, source states are justified to fear that their tax legal entitlement to tax foreign activities within their markets is steadily being curtailed. Furthermore, the anonymity of internet transactions means that internet activity is difficult to trace; residence states’ tax authorities too could lose their ability to detect taxable business activity. E-commerce ventures would be able to elude fiscal liability altogether.

With the destabilisation of the traditional concept of PE, attention has quickly shifted onto servers and web sites for their possible qualification as a PE. Can a server, telecommunications device (such as a cable used in transmission), computer terminal, or web page be considered a PE?

“A web site of an e-commerce business is a combination of software and electronic data stored on and operated by a server.”

Others have described a web site as “a company’s or an individual’s collected web documents”. It is clear from these two definitions that a web site is intangible and as such cannot alone make up a “place of business”. To satisfy the latter requisite, there has to be a facility such as premises or, in certain circumstances, machinery or equipment.

An internet server consists of tangible computer equipment networked to the internet. A server is usually dedicated to the storage and internet accessibility of web sites, email accounts and databases and software programmes resident on the server can automatically administer the electronic transmission of digitalised e-commerce products or services to end consumers. E-commerce ventures may use the web hosting services of ISPs who allocate and make available to them sufficient server space for their e-commerce requirements. Alternatively, such firms may own or lease a server so as to command a higher level of control over the server.

When a rational economic entity (whether individual or company) sells goods or services, the objective of such trade is to make a profit. The location of the entity itself and the means by which transactions are carried out are subject to the same overriding objective. An electronic means of doing business does not alter this objective, although it may create vast changes in the ways the objective is achieved. By and large the changes do not affect what is taxed (that is, the tax base – for example, company profits), therefore there is no need to make changes to existing systems. World-wide taxing authorities seem convinced that this is the way forward. At the Ottawa Ministerial Conference in 1998, which considered taxation framework conditions, the OECD agreed that taxation, in the way that it affects e-commerce should demonstrate the following qualities, namely neutrality; efficiency; certainty and simplicity; effectiveness and fairness; and flexibility (Fairpo, 2001; Ogley, 2001). These are basically the canons set out by Adam Smith. However, the general feeling from reports world-wide is that taxation issues surrounding electronic commerce should be considered very carefully before any action at all is taken. Many countries have actively appointed official bodies which have produced, or will produce, reports or recommendations. For example, Morrison (1999) reports that the general view taken by tax authorities in Australia and New Zealand is one of tax neutrality – that is, that a business or individual doing business over the Internet should not be taxed differently from how it/she/he would be taxed if they had used traditional means (see also Holland, 1998). Canada adopts a similar view (Niederhoffer, 1999). Israel is currently looking at the issues, and the Israeli Income Tax Commission has recently appointed a committee to examine the tax issues (Katz, 1999). The Netherlands have been particularly concerned about VAT (Keijers & Mermans, 1999). The UK has explicitly stated that it will work closely with the OECD in developing an international taxing regime for e-commerce, and the Joint Paper issued by the Inland Revenue and Customs and Excise on 6 October 1998 gave only outlines of the general principles which will be applied – neutrality (as for Australia, New Zealand and Canada), also certainty, effectiveness and efficiency (Kilby and Noroozi, 1999). Most countries seem to be holding off implementing major changes in tax laws at present, though the development of tax law in particular areas may have an impact as regards e-commerce, as in the UK with the regulations for controlled foreign corporations.

The idea seems to be to fit e-commerce transactions within the existing national frameworks, not treat them as something new, though making appropriate amendments for clarity (Maguire, 1999; Barlow, 1999). The UK certainly seems to be adopting this approach, though with no promises. Gabs Mahklouf, director of the Inland Revenue’s International Division, though speaking about maintaining the idea of the permanent establishment (PE), said recently that no one knows enough about how ecommerce will develop to make reasoned decisions on whether to abandon an established mechanism or not. This could be true of many tried and tested means of applying tax (Griffiths, 2000). Some countries appear ill-equipped to deal with any aspects of e-commerce. Mexico, for example, lacks a detailed tax infrastructure (Amante & Pena, 1999), and is likely to take many years to put in place appropriate regulations, despite a great and growing interest in e-commerce. The electronic marketplace in Germany is in a relatively early stage of development compared with other European countries, so there is little in the way of guidelines or national reports (Eiker, 1999). The literature (partly summarized above) reveals particular areas which are of common interest to all tax jurisdictions – residence, source of income and permanent establishment concepts; characterization of income; transfer pricing and the use of tax havens; controlled foreign corporations and activities of residents overseas; goods and services taxes (including VAT or those particular to a jurisdiction, like Provincial Sales Tax (PST) in Canada); customs; administration and compliance. Boyle et al. (1999) provide a commentary on the various aspects under consideration. They conclude that the idea of a permanent establishment or nexus (which is much discussed – see also Levin and Pedersen, 2000; Levine and Weintraub, 2000) is flexible and can be applied to e-commerce transactions. Essentially business over the Internet can be reduced to the idea of communicating. In the past, posting an order from overseas did not mean that a permanent establishment was in any way created to achieve the business. Ordering via a website (even with the notion of a server located in a country to facilitate this) is similar to the older model of ordering goods, so can be incorporated within existing models. The idea of a permanent establishment is well understood world-wide. Mere visibility does not give rise to a tax nexus. A website or server does not constitute the operation of a business – unless a substantial amount of capital or human resources accompany it. It can be deemed preparatory and/or auxiliary, and thus escapes. Boyle et al. (1999) disagree with a recent court decision in Germany where an unmanned oil pipeline was treated as a permanent establishment and gave rise to tax liability in Germany for the foreign owners. Where transactions take place, or are deemed to take place, can be very problematic. McDonald (2000) gives an example of a US business person, on holiday in Holland, downloading a £500 computerbased training course from a UK supplier’s website on to his laptop. Should he pay import duty on reentry to the US? Should the UK supplier charge (or not) output Value Added Tax (VAT) on the grounds that it was sold to a US resident? If VAT is in issue, is it UK VAT, or has the UK company made the supply in Holland, and so should charge Dutch VAT? What sort of evidence would a taxing authority need to determine jurisdiction? There are several different ways to look at this, but it is not beyond resolution with clearer guidelines. A US citizen will have bought goods in both Holland and the UK before, hence there is a clear starting point for resolution. Boyle et al. (1999) go on to consider the characterization of transactions and conclude that e-commerce transactions should be characterised in the same way as conventional transactions, though they do acknowledge that definitions may be blurred as ecommerce develops. Under this heading they consider the case of an encyclopaedia. If delivered electronically, it is still the same transaction as if delivered as a physical set of books. However, income from the provision of access to an on-line database including the same information contained in a conventional encyclopaedia may appear more like income from the rendition of services, especially if the information is updated frequently or if the database allows the user to search and organise the data

according to his/her needs. Generally there should be no problem if the conventional form of delivery is taken as a guide. If goods are delivered electronically, they can still be seen as goods, not intangible property giving rise to royalties. This maintains neutrality between electronic forms of business and conventional ones. If a transaction exhibits several different facets within itself, then the predominant character rule will apply – again something which is not new. Principles appertaining to the source of income will be straightforward for many e-commerce transactions (generally depending on residence), and in service cases, the guiding principle should be that income is sourced where it is created, not where the consumer is located. There is nothing new here. For example, consider the case of a New York lawyer who provides legal services to a UK client: there is no question that his income arises in the US.There are some slightly arcane issues – such as it being important to determine the activities of the service provider – which are relevant to ascertaining where income is generated. The US/Mexican Piedras Negras case is often cited, where the source of revenue from broadcasting depended on the point of transmission of the broadcast. However, the real substance of the case was that the Court looked at where the value was created for the business, and decided that this was the point of broadcast. Websites operate differently, so this principle may not be applicable.

Boyle et al. (1999) also consider the activities of agents or contractors, transfer pricing and withholding taxes. They conclude that existing regulations, perhaps if better defined, can deal with the situations likely to result from e-commerce transactions, though it will depend on the direction taken by ecommerce developments, but because this is so nebulous and fast changing, this is a very uncertain area – and is likely to remain so.

The OECD (2001) published a series of reports on its website produced by various Technical and Advisory Groups (TAGs) to deal with the newer issues created by e-commerce (see KPMG, 2001). These address, among other issues, the clarification of applying the permanent establishment concept; attribution of profit to a permanent establishment; treaty characterization issues concerning income/payments; and where indirect taxes should be applied. Spain and Portugal have dissented from the conclusions produced on clarifying how to apply a permanent establishment concept, so while most OECD members may broadly agree, there are still differences arising.

However, the thrust of these reports is to take existing ideas or concepts and adapt them to e-commerce issues.

The Internet has radically altered the potential for international business development. The ways in which e-commerce in SCM continue to evolve will be crucial for tax considerations. In terms of theoretical considerations, the current situation must be regarded as unsatisfactory. First of all, there is now a need for tax jurisdictions to take an international perspective as well as their customary national one. While this is something that has been gradually developing with the increasing globalisation of business, until the development of the Internet it has not been necessary for jurisdictions to the degree it is now. Because of this, the theoretical considerations underlying imposition of taxation must likewise be looked at internationally. It must be remembered that world-wide, business is in transition. Not everyone is currently doing business via the Web, and while there is a move towards this, no one is as yet able to say just how far this will develop. In terms of equity, not all entities are treated the same.

Cases may now come before the courts in an attempt to clarify how nebulous e-commerce in SCM issues should be better defined and/or taxed, but almost certainly there would be more if new laws were to be written from first prin- ciples to deal with e-commerce. The existing national systems will have to remain and develop to deal with new situations, as they have always done, possibly by new statutes, definitions, and case law acting as precedent. The latter particularly is a tested, traditional way of dealing with issues about which no (clear) legislation exists.

Amante, G., Pena, S. (1999) Permanent establishments: Mexico. International Tax Review, 10(7), IX–XIV.

Attorney, G. (1998) Report of the Electronic expert Group to the, Electronic Commerce: Building the Legal Framework, www.law.gov.au/aghome/advisory/ecag/single.htm.

Barlow, D. (1999) VAT aspects of e-commerce. International Tax Review, September(Suppl.), 40–43.

Bennett, R. (1997) Export marketing and the internet: experiences of web site use and perceptions of export barriers among UK businesses. International Marketing Review, 14(5), 324–344.

Boyle, M.P., Peterson, J.M. Jr., Sample, W.J., Schottenstein, T.L., Sprague, G.D. (1999) The emerging international tax environment for electronic commerce. Tax Management International Journal, 28(6), 357–382.

Cavusgil, S.T., Knight G.A. (1997) Explaining an emerging phenomenon for international marketing: global orientation and the born-global firm. Working Paper, Michigan State University CIBER.

Chetcuti, J.-P. (2003). The Challenge of E-commerce to the Definition of a Permanent Establishment: The OECD’s Response, http://www.inter-lawyer.com/lex-e-scripta/articles/e-commerce-pe.htm#_ftn1

Davies, L.J. (1998). Model For Internet Regulation www.scl.org/content/ecommerce

Eiker, K. (1999) Germany. International Tax Review, September(Suppl.), 54–56.

Fairpo, A. (2001) E-commerce – taxing internet trade. In Taxline Tax Planning 2000–2001, eds F. Haskew and F. Lagerberg, pp. 60–69. Faculty of Taxation of the Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales, London.

Griffiths, B. (2000). E-business – where would you choose? Accountancy Age, 20, 8-9.

Hamill, J., Gregory, K. (1997). Internet marketing in the internationalisation of UK SMEs. Journal of Marketing Management, 13, 9–28.

Holland, G. (1998) Electronic commerce – taxation framework considerations. Chartered Accountants’ Journal of New Zealand, 77(10), 41–42.

Johanson, J., Vahlne, J. (1977). The internationalisation process of the firm – a model of knowledge development and increasing foreign market commitment. Journal of International Business Studies, 8(2), 23–32.

Johanson, J., Vahlne, J. (1990). The mechanism of internationalisation. International Marketing Review, 7(4), 11–24.

Johanson, J., Wiedersheim-Paul, F. (1975).The internationalization of the firm – four Swedish cases. Journal of Management Studies, October, 305–322.

Katz, Y. (1999). Israel. International Tax Review, September(Suppl.), 65–67.

Kedia, B.L., Harveston P.D. (1999). The role of mindset in the internationalization process: a comparison of born global and gradual globalizing firms. In S.L. McGauhey, S.J. Gray and W.R. Purcell (eds) International Business Dynamics of the New Millennium: Proceedings of the 1999 Annual Conference of the Australia – New Zealand International Business Academy, pp. 109-120.

Keijers, R., Mermans, P. (1999). The Netherlands. International Tax Review. September(Suppl.), 74–76.

Kilby, J., Noroozi, A. (1999). United Kingdom. International Tax Review, September(Suppl.), 74–76.

Levin, L.D., Pedersen, R.C. (2000). When does e-commerce create a PE? The Tax Adviser, 31(5), 306–309.

Levine, H.J., Weintraub, D.A. (2000). When does e-commerce result in a permanent establishment? The OECD’s initial response. Tax Management International Journal, 29(4), 220–229.

Maguire, N. (1999). Taxation of e-commerce: an overview. International Tax Review. September(Suppl.), 3–12.

Mangiaracina, R., Marchet, G., Perotti, S., Tumino, A. (2015). A review of the environmental implications of B2C e-commerce: a logistics perspective. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 45(6), 565-591.

McDonald, G. (2000) http:/www/just.how.risky.is.the. internet? Management Accounting, 78(3), 74–75.

Morrison, J. (1999) Australia and New Zealand. International Tax Review, September(Suppl.), 44–47.

Niederhoffer, J. (1999) Canada. International Tax Review, September(Suppl.), 48–53.

Nightingale, K. (2000) Taxation Theory and Practice 2000–2001 (3rd ed). Prentice Hall, Harlow (UK). OECD (2001) Technical Advisory Group reports at www.oecd.org/daf/fa/e—com/public—release.htm

Ogley, A. (2001) International outlook: e-commerce and OECD. Taxline, March, 12–13.

Oviatt, B., McDougall, P. (1995) Towards a theory of international new ventures. Journal of International Business Studies, 25(1), 45–64.

Rankin, K. (1999) More worries for Y2K, and beyond. Discount Store News, 38(15), 13.

Rowland, D., Macdonald, E. (2000). Information Technology Law, 2nd edition, pp. 251-252

Rogers, A., Taft. D.K. (2000) Politics as usual. Computer Reseller News, 27, 3, 16.

Smith, A. (1776). An Enquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, Cannan edition (Modern Library), 1789 edition.

Srirojanant, S., Thirkell P. (1999) Driving international business performance through use of internet technologies: a survey of Australian and New Zealand exporters. In International Business Dynamics of the New Millennium: Proceedings of the 1999 Annual Conference of the Australia–New Zealand International Business Academy, pp. 250–275.

Sweetman, S. (2003). A Short Practical Note on E-Commerce and Tax — TaxationWeb. http://www.taxationweb.co.uk/businesstax/ECommerce_Taxation.pdf

Taft, D.K., Rogers A. (1999). E-commerce tax rears its ugly head. Computer Reseller News, 23(586), 1–2.

Yu, Y., Wang, X., Zhong, R. Y., Huang, G. Q. (2017). E-commerce logistics in supply chain management. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 117(10), 2263–2286.

Wang, Y., Wallace, S. W., Shen, B., Choi, T.-M. (2015). Service supply chain management: A review of operational models. European Journal of Operational Research, 247(3), 685–698.

Sawik, T. (2014). Optimization of cost and service level in the presence of supply chain disruption risks: Single vs.multiple sourcing. Computers & Operations Research, 51, 11–20

1. Al Ain University of Science and Technology, Al Ain, UAE, ahmed2019adel2019@gmail.com

2. Al Ain University of Science and Technology, Al Ain, UAE