Vol. 38 (Nº 34) Año 2017. Pág. 28

FRACALANZA, Paulo S. 1; CORAZZA, Rosana I. 2

Recibido: 20/02/2017 • Aprobado:21/03/2017

3. The working time reduction in perspective

4. The rebuilding of worker’s identity in consumption culture

ABSTRACT: In 1930, Keynes wrote the essay Economic Possibilities for Our Grandchildren, predicting that in a century, due to the advancements of technical progress and productive forces, humankind could be free from excesses of workload. An era of abundance and freedom would come and humankind could dedicate to ideals of a good life. In this paper, we propose to identify some reasons why the world described by Keynes did not materialize and seems far away from the contemporary reality. |

RESUMO: Em 1930, Keynes escreveu o ensaio Possibilidades Econômicas para Nossos Netos, prevendo que em um século, devido aos avanços do progresso técnico e das forças produtivas, a humanidade poderia estar livre de excessos de carga de trabalho. Uma era de abundância e liberdade viria e a humanidade poderia se dedicar aos ideais de uma vida boa. Neste artigo propomos identificar algumas razões pelas quais o mundo descrito por Keynes não se materializou e parece distante da realidade contemporânea. |

In 1930, in the middle of shock of 1929 Crisis, Keynes published at The Nation and Athenaeum an essay called Economic Possibilities for Our Grandchildren.

Already on first lines of his text, Keynes intended to provide some optimism facing what he called ‘two opposed errors of pessimism’ back then. Firstly, the pessimism mistake of revolutionaries, ‘who think that things are so bad that nothing can save us but violent change’ (Keynes, 2008, p. 18). The second mistake, the reactionaries one, for whom ‘the balance of our economic and social life [would be] so precarious that we must risk no experiments’ (Keynes, 2008, p. 18).

Two years before it, Keynes had already held a conference about this subject for an audience of undergraduates of Cambridge. His target was clear: Keynes observed with preoccupation an inclination of many of his students to socialism, which seemed to them a promising alternative to build up a fairer and potentially more libertarian social order.

In his view, there would still be good fruits in capitalism and the crisis would only be the manifestation of growing pains of over-rapid changes that must not be confused with ‘rheumatics of old age’. Even world depression and ‘unemployment abnormality in a world full of necessities’ (Keynes, 2008, p. 18) must not blind men for more important tendencies that were being produced under most apparent surface of phenomena.

He assured in an ironic way that in over one hundred years, owing to spectacular advancements of technical progress and huge potential of productive forces in capitalism, humankind could finally be free from oppression of its most primitive ‘economic problem’: the work burden in fighting for survival. Thus, it would come the time of abundance and freedom and people could finally devote to ideals of a full, happy, wise and good life.

However, our author did not believe that crossing to this paradise would be made without obstacles. Some restrictive conditions would have to be met:

(…) our power to control population, our determination to avoid wars and civil dissensions, our willingness to entrust to science the direction of those matters which are properly the concern of science, and the rate of accumulation as fixed by the margin between our production and our consumption; of which the last will easily look after itself, given the first three. (Keynes, 2008, p. 25-26).

However, until prosperous times happen, humans should continue to pretend that ‘fair is foul and foul is fair; for foul is useful and fair is not’ (Keynes, 2008, p. 25). Consequently, most of humankind should follow directing its impulses towards heteronymous, arduous and ceaseless work whilst capitalistic class should insist in idolizing the golden calf and enlarging their wealth by simple pleasure to accumulate it.

In an inspired allegory, which we believe express well the meaning of his message, Keynes would have flirted with what Skidelsky & Skidelsky call a Faustian bargain: even though Keynes disliked capitalism and detested the man forged in this environment - in his human condition of a mere automaton - he claimed that this would be the price to be paid for a system of social relationships that orchestrated the impulses of people to the domain of productive forces, for the advancement of material progress and for the inconsiderate accumulation of wealth. The time would come, he longed, in which humankind, fully equipped with all the means to meet its needs with little input of human labor, would unfold new and better directions to life.

Even his reconnaissance of injustice of such unequal appropriation of economic surplus also seemed to be justified in terms of the diabolic pact: if it was conceded to working classes little or more than required for its reproduction, all excessive work – if discounted, undoubtedly, what would be sacrificed by conspicuous consumption of wealthy classes – could be destined to wealth accumulation. (Keynes, 2007).

Nevertheless, we must not imagine our author was naive. Keynes knew well – or at least it is how we read him – that his speculations, or it would be more appropriate to say, his aspirations, were within a utopian dimension, as their possibilities to happen would fundamentally depend on unsuspected paths that humankind would eventually decide to build. Furthermore, perhaps we would add, in a tone that would become bitter throughout the years, that his essay was not properly interpreted: he never wanted to give false hopes. His purpose was deride, with sophisticated irony, the destiny that humankind created for itself. We believe this is a legitimate interpretation of Keynes’ wisdom at least for three reasons.

The first resides in discussion on unlimited character of human desires. Keynes claims that it is fundamental in this matter to distinguish between absolute and relative necessities: the first ones are those felt regardless of third parties’ situation. The last ones are experienced because of a comparison with third parties’ situation. The first ones can be satiated, whilst the last ones can be insatiable. We believe this distinction makes it clearer the meaning given to the idea of accumulation rate, calculated as a margin between production and consumption: if humankind were guided by mirage of liquid, elastic, relative, insatiable desires, it would be impossible to solve the economic problem.

The second one is due to all types of ‘psychological’ obstacles – or perhaps it would be more convenient to say, obstacles rooted in socialization forms and institutions and requirements of Western culture – in the way of creating a world without work. In this regard, many questions arise: how people would reorient their instinctive passions, mostly domesticated by means of exhausting work? Would Man be capable of killing his inner Adam? So, in this case, to what Man would dedicate to? For Keynes, judging from the achievements of elites, which experienced a world without work, the prognostics were not encouraging. In implacable terms:

To judge from the behavior and the achievements of the wealthy classes to-day in any quarter of the world, the outlook is very depressing! For these are, so to speak, our advance guard – those who are spying out the promised land for the rest of us and pitching their camp there. For they have most of them failed disastrously, so it seems to me – those who have an independent income but no associations or duties or ties – to solve the problem which has been set them. (Keynes, 2008, p. 23).

In Keynes’ conception, the economic wealthy classes offered a depressing outlook in wasting their free time and potentialities in favor of status competition and unrestrained rivalry for possession of conspicuous consumption symbols.

The third reason grounds to the fact that Keynes, as well as Marx, conceived the nature of capitalistic economic system could not be apprehended in circulation sphere, the realm of interaction between free producers moved by consumption wish and their inner willingness to interchange goods. The revelation of the nature of our particular way of social organization required to reveal the constitutive asymmetry of power in all social relationships and the prevalence of wealth owners’ decisions in shaping life conditions of most of humankind. It must not be forgotten that when he wrote General Theory, six years later, Keynes would deride the irrelevance of conventional wisdom on the problem of work determination. When he stated the precedence of spending decisions of capitalists over income and employment volume in an economy, he assured that the employment volume was not determined within the limits of work market and it was absolutely irrelevant the workers’ pretenses to offer their workforce when demand conditions did not recommend to hire.

Economic Possibilities for Our Grandchildren has been revisited in recent years, to some extent because in 2008 Crisis, and Keynes was rehabilitated as the Master that supposedly had the keys to understand the origin of crisis and ways of mitigating it. However, others have looked in this essay for answers to their astonishment in a world, especially in Western rich countries, where the blossoming of human autonomy and possibilities did not follow accumulation of material wealth.

After over 80 years of publishing this essay, it is necessary to acknowledge that humankind not only did not reach the requisites of a good life, but also established a form of social organization where ‘money love’ became common – and even morally desirable – and when daily workload attained unsuspected levels. Our objective, within the limits of this paper, is investigating, starting with a rich contemporary literature, the evolution of workload within last years and question some of reasons why the new world described by Keynes did not happen and it seems even more distant from ever happening. Therefore, the employed methodology consists in critical revision of arguments by authors selected for their recent contributions in this subject, some of them are Schor (1992, 2010), Skidelsky (2010), Skidelsky & Skidelsky (2012), Dostaller (2009) and Jackson (2010).

To prepare this essay, in addition to this introduction, we believe some key matters must be addressed. Firstly, it must be brought to the center of stage, in a second topic, the political dimension of fighting for working hours and question why those ways of fighting seem not to mobilize workers’ wishes and aspirations anymore.

In a third topic, it must be made an assessment of a trend identified by influential researchers in many countries of an increase (or block of secular reduction trend) of working time durations and preponderance of more acute heterogeneity among workers with regard to workloads extension.

Finally, in a fourth topic, and as a conclusion, it is intended to question the reasons why, within Keynes terms, we did not get to overcome the ‘economic problem’.

What impressed Keynes and many observers of economic and social phenomena under capital regime was irresistible force of material progress – of limitless growth of work productivity under ceaseless rhythm of technical progress and work discipline. To give voice to another author, his contemporary, we observe how Schumpeter mentions the evolutionary character of capitalism under impulse of innovations, something that in his opinion did not escape from Marx:

Capitalism, then, is by nature a form or method of economic change and not only never is but never can be stationary. […]

[…] [This is the] process of industrial mutation – if I may use that biological term – that incessantly revolutionizes the economic structure from within, incessantly destroying the old one, incessantly creating a new one. This process of Creative Destruction is the essential fact about capitalism. It is what capitalism consists in and what every capitalist concern has got to live in. (Schumpeter, 2003, p. 83).

Landes would complete it agreeing with Schumpeter, in his monumental The Unbound Prometheus:

The result has been an enormous increase in the output and variety of goods and services and this alone has changed man’s way of life more than anything since the discovery of fire: the Englishman of 1750 was closer in material things to Caesar legionaries than of his own great-grandchildren. (Landes, 2003, p. 5)

It must not be attributed any naivety in Keynes’ thought. The terms of a Faustian bargain in the sense that Skidelsly & Skidelsky gave to the term, in other words, the idea that, in the name of a promise of full life, most humankind must be sacrificed to work without end did not escape our author. In The Economic Consequences of The Peace, the rudeness of this argumentation is offered without disguise:

The immense accumulations of fixed capital which, to the great benefit of mankind, were built up during the half century before the war, could never have come about in a Society where wealth was divided equitably. The railways of the world, which that age built as a monument to posterity, were, not less than the Pyramids of Egypt, the work of labor, which was not free to consume in immediate enjoyment the full equivalent of its efforts. (Keynes, 2013).

Even more than that, Keynes admitted that growth of this extraordinary system –the Capitalist System – depended of success of a double bluff. On the one hand, the working masses must accept ‘from ignorance or powerlessness, or were compelled, persuaded, or cajoled by custom, convention, authority, and the well-established order of Society into accepting’ a small part of wealth socially produced. (Keynes, 2013). On the other hand, it would be wealthy classes’ responsibility, in interest of wealth accumulation, to devote to virtues of ‘saving’ and austerity. Nevertheless, the background question would have to be revealed: What if the cake really grew? The fact is that Keynes did not have much hope that humankind would know how to use this bless:

(…) so the cake increased; but to what end was not clearly contemplated. Individuals would be exhorted not so much to abstain as to defer, and to cultivate the pleasures of security and anticipation. Saving was for old age or for your children; but this was only in theory,—the virtue of the cake was that it was never to be consumed, neither by you nor by your children after you. (Keynes, 2013).

If we abandon our Cambridge author and read Marx, some of mentioned subjects would get a more encouraging perspective. An attentive reading of eighth chapter of The Capital enables to evidence an argument barely explored by some economists that deal with the matter of reducing working time: that increasing work productivity and the degree of work intensity create an even bigger exceeding time grandeur. Everything more being constant, and without prejudice of rate of surplus value, this extra time can have four non-exclusive destinations: it can be reinvested; it can be used to expand the basket of goods consumed by workers, or luxury goods at the disposal of capitalist classes; it can be appropriated by the State; or it also can represent the opportunity for reducing working time.

However, in capitalist production, the growth of workforce productivity does not aim to reduce the working time. The constant tendency of capital to develop workforce productivity has the purpose of reducing the amount of workforce and, consequently, enlarging the surplus value, providing a new impulse to capital valorization process.

Thus, a reduction in working time duration, movement not included in capital regime, can only happen, at first, as a product of workers’ resistance, because of the struggle of the working class. However, this resistance presuppose that workers are organized and, for this purpose, it is fundamental that working class have a certain density, in terms of its contingent and proportion, and gather political power.

Then, it is required to bring to the center of stage the political dimension of the struggle for definition of working time in terms employed by Marx. This means that the regulation forms of working time are historically a multi-secular fight by working class, on the one hand, and by capitalist class, on the other hand, for defining the limits of working time duration.

Consequently, we must not be astonished that the first movements to reduce the working time and appearance of first laws that attempted to discipline working time duration showed up in England, the cradle of first labor unions.

Without ignoring the threat that growing workers’ movement offered, Marx seem to prefer the interpretation that it is by force and State initiative that working time was limited in England’s factories. Opposing the first English factory laws to réglement organique of Danubian reigns, Marx concludes that the willingness of English State to regulate the extension of working hours owed to a rational calculation. The intolerable limits to which it reached in England ‘torn up by the roots the living force of nation’ (Marx, 1909, p. 264). The roots, in this context, is a metaphor for child labor and it will be exactly children the first targets of factory laws in English soil.

Summing up the steps of our investigation, we observe that in our social organization under capital regime, the technical progress and intensification of workload are required conditions, but not enough, to lead to a reduction in the working day. The particular form of sharing this extended economic surplus depends on a number of factors, some of which being: the evolution of work productivity, the correlation of forces between capitalists and workers and the way the State intervenes in economic activity regulation.

This historical process of fighting on the limits of working time had different consequences as time went by and many advances were effectively accomplished to define exploration limits. It is required to ask why nowadays the work world seems to be so fragmented with regard to the extension of working time and why those ways of fighting that were important strategies of labor union movement for a long time are blurred and seem not to mobilize workers’ wishes and aspirations anymore.

Effectively, if we observe a long historical period, we will have a contrasted view on the extension of working time. In the dawn of capitalism, between XIV and XVIII centuries, moment of the sprouting of British Industrial Revolution, working time progressively extended and reached, by the end of XVIII century, unendurable limits. Not by coincidence, through that long period, as machinery made muscular strength dispensable, the use of workforce of women and children turned to be extensive.

However, in the opposite way, when it is gathered available statistics on annual effective duration of work at developed countries, one observes that within the last one hundred and fifty years there was an important reduction in working time. Although the reduction is unquestionable for the group of industrialized countries, Huberman (2002) suggests that in periods of greatest economic prosperity the reduction of workloads was more significant, such as in periods after First and Second World Wars. On the other hand, the periods of intense turbulence, especially from 1929 to 1950, were followed by a fluctuation and sometimes even an extension of working time duration.

Thus, if we are seduced by the myth of progress of our era and generous promises of conquers by science and technology we could be tempted to imagine that the reduction of working time will follow an inevitable path.

Nevertheless, concretely, in historical reality lived in each country the effective limits of working time duration have a great heterogeneity. Some factors that contribute to dispersing working times comprise, amongst others: i) The legal institution of legal orders of protection to work and delimitation of working time extension ; ii) The ways of managing working time and extension of working time actually performed in work places ; iii) The architecture of public policies towards the work market ; iv) The political strength of labor union movements and their claim strategies ; iv) The heterogeneity of wage employees with regard to ways of hiring and compensation; vi) The collective aspirations of employees to choose between the increase of free time and increase of purchasing power ; vii) The social inequality and not only with regard to inequality of income and wealth, but also the inequality to access jobs and stable and secure positions in labor market.

If a wide analysis of statutory limits for working time duration worldwide shows a convergence of legal work week to the standard of 40 hours, the effective average durations of work, having the week as reference, presents a much more diverse scenario: for a group of countries, the durations range from 35 to 45 hours, although it is often observed countries where the workloads exceed 48 hours a week. In this regard, in 1992, Juliet Schor, in The Overworked American, warned that American workers were working more and more and many of them, despite joint efforts of spouses, were tied to an insidious spiral of increased work and growing debts.

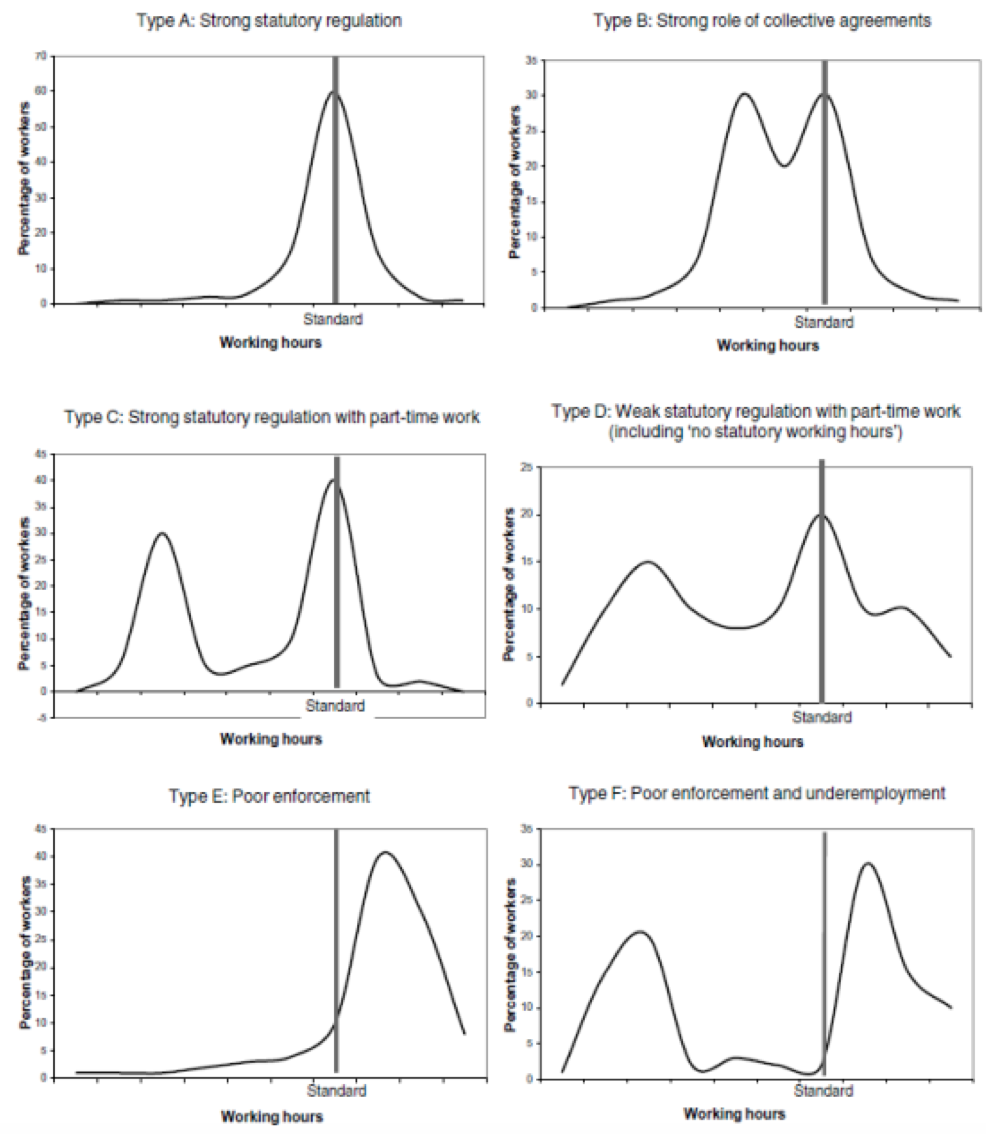

Nevertheless, more than observing average grandeurs, it is fundamental to observe the heterogeneity of work durations among individuals. Lee, McCann and Messenger (2007), grounded in analysis of questionnaires sent by International Labor Organization (ILO) to national statistics agencies, gathered evidences for 62 countries. The analysis of those data, very original, enabled to observe many types of dispersion standards among effective weekly durations of work in the level of individuals and we believe their exposure is inescapable.

Source: Lee McCann and Messeger (2007)

In countries where sectoral collective bargaining is important and also where effective limits to restrict the duration of working time of non-unionized workers are enforced – such as Germany and Austria –, there may be a distribution of frequency with two peaks, one around defined legal standards and another relatively lower, that expresses the results of sector agreements. The graph under title of type B displays such pattern.

The graph under title type C depicts a third pattern, observed in Belgium, a country that strongly observes statutory standards and where part-time jobs are very common.

A fourth possibility (type D in graph) is the one of United Kingdom and Japan, where regulation of working time is weak, the option for part-time jobs is frequent and where a significant proportion of workers endure working time durations above the legal definition of weekly workloads.

A fifth standard would be typical of developing countries, as well as some developed ones like South Korea and United States, where statutory regulation is weak, so that most workers are carrying out working hours in average beyond the standard of 40 hours (type E). As an example, in the USA the absence of a legal standard to rule the maximum amount of overtime makes ineffective the guidelines for normal workloads.

Finally, a sixth type is developed in countries that have a weak performance of labor market and little effectiveness of statutory regulations, with many employees subject to greater workloads or situations typical of underemployments, in informal situations with short, intermittent and badly-paid workloads, which is represented in graph above under type F.

But if analysis shown above grounded in extensive group of data explored by Lee, McCann and Messeger (2007) have the undeniable merits of evidencing the heterogeneity of working time extensions lived by occupied workers, it is required not to forget that the actual inequality situation is even more worrying. Unequal sharing of work volume takes on more serious features when it is included in statistics the unemployed and discouraged workers. Nowadays, unemployment rates among youths in many European countries show the unsustainability of socially forged standards. If work is denied to youths in a society, ‘(...) where attributes connected to work to characterize the situation that classifies the individual in the society seem to have been definitely imposed rather than other identity supports, such as family or registration in a community’, as it would be put by Castel (1995, p. 385), what remains, then?

This is a crucial moment of crisis in the work world and the evidences are even more conspicuous that we live in a world of two speeds (à deux vitesses) as warned by Gorz (2007). Not surprisingly, many authors resumed the proposal of reducing the working time in terms very similar to those suggested by Gorz, although with different focus, such as the concept of sufficiency and the ideals of a full, wise and good life beyond the market (Skidelsky & Skidelsky (2012); Schor (2010), Jackson (2010)). The idea here is opposing to impeccable logic shown by Gorz that ‘the unlimited maximum inefficiency in capital valuation required then the unlimited maximum of inefficiency to provide necessities and waste in consumption’ (Gorz, 2007, p. 115).

Therefore, this subject addressed in final section of this paper.

Now it is true that the needs of human beings may seem to be insatiable. But they fall into two classes – those needs which are absolute in the sense that we feel them whatever the situation of our fellow human beings may be, and those which are relative in the sense that we feel them only if their satisfaction lifts us above, makes us feel superior to, our fellows. Needs of the second class, those which satisfy the desire for superiority, may indeed be insatiable; for the higher the general level, the higher still are they. But this is not so true of the absolute needs – a point may soon be reached, much sooner perhaps than we are all of us aware of, when these needs are satisfied in the sense that we prefer to devote our further energies to non-economic purposes. (Keynes, 2008, p. 21)

The hierarchy between absolute and relative necessities that Keynes mentioned in aforementioned paragraph evidences, in the one hand, that he recognizes that some human necessities are insatiable. The possibility of having part of those necessities satisfied constitutes, as we have already mentioned in this paper, one of the conditions to resolve the ‘economic problem’. Growing necessities – or wishes –, established and reshaped in a dependent way by the consumption behavior of third parties, would place humankind in an eternal treadmill, in which all effort will led only to the acceleration of the speed without allowing it to move.

In this session, we address the understanding of some of the reasons that would explain why humankind still could not overcome what Keynes called economic problem, focusing on the connections between work and consumption. Why, at this stage of development of productive forces, human being would not have reached the circumstance predicted by Keynes of being able to work only some weekly hours?

To answer to this question, an analytical look is inspired by reflections on consumption subject provided by selected authors: the notion that ‘the context matters’ by Robert Frank; the interpretation that ‘goods communicate, create identities and define relationships’ of Mary Douglas and Baron Isherwood; the ‘inverted chain’ view by John K. Galbraith and the ‘creation of wishes’ by Vance Packard.

Robert H. Frank, Economics professor of Cornell University and scholar of matters related to the consumption world, was surprised with the fact that Keynes gave such little importance in his Economic Possibilities to the so-called relative necessities. Frank (2008) emphasizes the role of context in modeling demand. He defends that demand by ‘quality’ in any domain would always be universal and inevitable. An example taken by Frank on universality of this wish for quality comes from cars: the progressive and ceaseless incorporation of technology and upper levels of comfort are being spread from most expensive models to simplest ones. A second example, on advancements in qualities of bicycles - with more sophisticated models, incorporating new materials, as carbon fiber, parts in aluminum, Shimano brakes and an important number of more or less extravagant accessories - must reinforce the idea that this wish for quality is present in the most different goods. A general notion present in this reasoning would be that, at first, every demand would have a relative dimension in terms of quality of goods or services that could supposedly meet it. Frank (2008) shows the example of a ‘good school’ to illustrate how this notion is, once again, dependent on the context:

‘[...] the concept of a ‘good’ school is inescapably relative [...]. In most jurisdictions, after all, school quality strongly correlates with the average price of houses in the corresponding neighborhoods. There are perhaps no expenditure categories for which context is more important than those that assures that our children will enter adulthood successfully. And buying a house in a safe neighborhood with good schools is perhaps the most important of such expenditure’ (Frank, 2008, p. 149).

To freely re-elaborating the proposition of Frank (2008), we would say that his view on work urgency is such that it remains when the nature of the economic problem is understood as a requirement that is enlarged by quality wish. In addition, the perception of what does ‘quality’ mean depends on the context, and the context, on its turn, corresponds to the social circumstances that surround consumption decisions and the advent of strategies that come from the production side. Those are, for instance, technological advances and other strategies that multiply the alternatives to any goods and services, from diet to transport, from living to leisure, from education to culture. Thus, facing a context of offers where qualitative wealth expands, the Adam part in each one of us remain. The necessity of a quality consumption compels us to work. Would Keynes have been oblivious to this reason?

Nevertheless, the wish for quality can be analogous to wish for different goods. Let us take the case of the consumer electronics as an example. The qualitative enlargement in terms of models and design, together with emergency of new functionalities in more different products, is an example of how novelty feeds the wish treadmill. A new stereo sound system, a new cell phone or any other durable good – the object – can be so fascinating that the ‘subject’, possessed by desire, soon leaves behind something similar he has just purchased in order to get another one. This is the nature of Lipovetsky´s hyperconsumption. The French philosopher took on the task of explaining the man in contemporary world by addressing, inter alia, the spheres of production and consumption (Lipovetsky, 2007).

A peculiar innovation, the credit card – along with other similar novelties such as retail store cards and gas, fuel or fleet cards – turned out to be an invaluable advance to boost capital accumulation in contemporary world, by two phenomena that are two faces of the same coin. On the one hand, the consumption dissociation from present income. On the other hand, without which the former would not be possible, the outbreak of a new cultural feature that intensely and increasingly marks the contemporary society: the overcoming of ascesis and prudence as prevalent behaviors with regard to the management of expenditures by a new ethos. The new ethos of thoughtless spending and the corresponding prodigality of fruition even before the availability of income (Manning, 2000).

The stubborn and relentless momentum of the insatiable desire of consumption, as stated Lipovetsky (2007), hovers above any other will or, as perhaps best suited, substantiates any other wills, such as belonging and communicating, as suggested by Douglas & Isherwood (2006). This momentum takes place in the determination of spending decisions and willingness to work in contemporary society, through of the full realization of this new ethos, in a particular way with the advent and widespread diffusion of credit card innovation.

In his book ‘Affluent Society’, Galbraith (1999) warned that the problem of capitalist society is that it produces excessively – especially, it produces excessively those goods supplied and consumed in the private sphere, rather than public goods and services, such as education, health and environmental quality. Galbraith saw in advertising the strategy to create the required demand to absorb all this excess of private goods. Almost one decade later, in the ‘The New Industrial State’, Galbraith mentions the ‘inverted chain’, where the producers create the demand, which is not, for that sake, the mere result of consumers’ preferences or wishes. Galbraith would say that producers are in charge of producing goods and services and, at the same time, creating demand.

In the previous year, Vance Packard, the restless American journalist and social critic, published ‘The Hidden Persuaders’, uncovering controversial techniques then employed by advertising and marketing professionals to persuade their audiences, both as consumers, in goods and services market, and citizens, in ‘political market’ with regard to their choices. Packard’s book (1957) became a best seller and shocked public opinion in mentioning the use of science by the advertisement industry: psychology, stimulus-response models, but also psychoanalysis, sociology and cultural anthropology. The focus of book is the so-called ‘motivational research’. In the first part of work, the author gives the word to the chief researcher of a company headquartered in Chicago who candidly summarize, to use the author’s expression, what motivation research is about:

“Motivation research is the type of research that seeks to lean what motivates people in making choices. It employs techniques designed to reach the unconscious or subconscious mind because preferences are generally determined by factors of which the individual is not conscious… Actually in the buying situation the consumer generally acts emotionally and compulsively, unconsciously reacting to the images and designs which in the subconscious are associated with the product”. (Packard, 1957, p. 35)

Thus, clarify the relationship between work and consumption demands the understanding of the motivation for the latter. In other words, it is required that one recognizes what frames the demands of contemporary society. In this matter, the works of Galbraith and Packard contribute to make clear the strategic character of ‘wish production’ in a context in which the accumulation cannot do without mass production - and mass consumption.

Another point we want explore in attempting to grasp the relationship between work and consumption and to get some clues of what would have drifted us so much away of a world with less working hours is the roles of goods beyond the satisfaction of ‘basic needs’. These roles, in the view of Douglas e Isherwood (1979), include the meeting of communication necessities, of creating identities and of establishing relationships. These other roles would have, according to the authors, to do with necessities that would also be met, at least partially, by goods and services, that is, by consumption.

In an essay published more recently, delivered in 2005, only two years before her disappearance at 86 years old, Mary Douglas, the prestigious British anthropologist, claims that ‘[...] for an implicit division of work, economists studied market economies and anthropologists studied gift economies’ (Douglas, 2007, p. 22). The author recounts her struggle to undo the theoretical notion of the ‘human person’ in economics. The anthropologist conceives a collective as the ‘unit’: the human being is a social being and if is committed to purchase a ‘basket of goods’, as it is proposed by macro or microeconomics, it would not be for his/her exclusive consumption. Even family consumption would be a limited idea of what Mary Douglas mean by ‘social’ and ‘collective’.

The author was invited at the end of 1990s to research on ‘current welfare philosophy, basic needs theories, human needs, quality of life, and results of researches grounded on them’ for a contribution within the discussion on Climate Change (idem, p. 23). It is a little bit of fun – but it also has something very, very tragic – to ‘see her’ disgusted with the precariousness of economic thought on the subject. She reports that all fragile economic perspectives start from Biology, by assuming a theory of needs that starts from physical ones, beginning with the living needs, as such of having food, water, shelter, etc. Being those needs met, the theory gives room to social needs, such as those of companionship and social and spiritual satisfaction. As Douglas (2007, p. 23) claims, ‘the theory should start with intelligent beings that have enough to live and even so let some of their fellows starve to death. ‘

Nowadays we live in a world of abundance. A world where excesses and waste are together with poverty. We have never been wealthier humans. Probably, we have never had so many helpless among us, beings of the same species.. Inequality is our characteristic. Those ‘without roof’, ‘without land’, ‘without work’ – the poor - divide the planet with a wealthy elite and with medium groups and workers, who share in an unequal way the works’ time and fruits. The bright future waited with a skeptical hope by Keynes almost eight and a half decades ago – the future that perhaps do not come to our grandchildren, is also the present denied to many of our contemporaries.

Mary Douglas’ ideas are simple – perhaps falsely simple – and brilliant, like a ‘Columbus egg’. Interested in Economic Anthropology, she has been to almost all her (long) life involved with economists. She liked some of them –such as Partha Dasgupta, for his critical ideas on economic measurement that ended up originating the Human Development Index. It seems that economists would benefit a lot from reading her work.

We can see below two sentences of her work that interest us when analyzing Economic Possibilities for Our Grandchildren (Douglas, 2007, p. 23-24):

“It has been said many things about communication, but always about individuals communicating: an inability to understand culture as a dynamic process made by interacting individuals. A psychology that conceived in a completely wrong way the Human’s nature is part of the burden with which a consumption theory has had to handle.

Rather than a table of basic needs that start with physical ones and finishes with social and symbolic ones, the opposite would work better.”

In this perspective, consumption in our societies, as in other previous social forms as anthropological knowledge can confirm, is vested with a role of structuring values, which are central to build up identities and for the regulation of social relationships.

Inside capitalism culture there is, side by side, a genius triad. The first of them is the one that watch for its incomparable historical capacity of producing goods – material or immaterial commodities. The second is the one able to inflate the desire of men and women to acquire these commodities, making it the insatiable longing that enables perennial consumption that frees and amplifies the continuous flow of production in a titanic scale. The third is what renders invisible, as if magically, all the complex social relations - lives, faces, bodies, roles, work, suffering and quirky bonds - that enable the existence of those commodities; this is the one that blurs the materiality of efforts and interactions engaged in the production that generates each of those commodities.

Belief in an ineluctable technological progress and the advancement of productive forces under capital regime has fed the hope that, sooner or later, humankind would end up in a situation of being able to solve the ‘economic problem’ – the fatigue of work in the struggle for life.

Events marking the work world these days seem not to endorse such good auguries.

We are in the paradoxical situation of producing wealth in abundance with huge efficiency and spending less human work, but not only fruits of socialized human work are badly distributed and in great extent absolutely superfluous – without mentioning harmful – as the magnitude of mobilized human work is also distributed unevenly.

Both in developed and underdeveloped world, one can see, in labor markets, side by side, men and women with wish and ability to work: some are granted full or undesirably extensive working hours, whilst others, exiguous working hours, and to still others, no work at al. Thus, it really comes as no surprise that many authors have been resuming the discourse and the proposals of reducing working time, a condition for a fairer share of produced economic surplus, but also a promise for a more fulfilled, wiser and good life.

Even if we are convinced that the reality in many countries is the misery in life’s most basic conditions for most of the population, perhaps it is urgent to bethink that there is no such thing as a human nature that impels us to insatiableness. On the contrary, now it is vital to recognize that a life devoted to the tireless search for goods is doomed to destroy its very best dispositions and skills. As Lafargue warned us (1883):

“A strange delusion possesses the working classes of the nations where capitalist civilization hold its way. This delusion drags in its train the individual and social woes, which for two centuries have tortured sad humanity. This delusion is the love of work, the furious passion for work, pushed even to the exhaustion of the vital forces of the individual and his progeny.”

Bluestone, B. & Rose, S. (1997). ´Overworked and underemployed´, The American Prospect, 31, 58-69, March-April. Retrieved from: https://www.msu.edu/user/dorman/bluestone1.htm

Castel, R. (1996). Les métamorphoses de la question sociale: une chronique du salariat. [The metamorphosis of the social question: a chronicle of wage]. France: Editions Fayard.

Cette, G. & Taddei, D. (1997). Réduire le temps de travail: de la théorie à la pratique. [Reduce working time: from theory to practice] Paris: Le Livre de Poche.

Dostaler, G. (2009). Keynes et ses Combats. [Keynes and his Battles] Paris: Éditons Albin Michel.

Douglas, M. & Isherwood, B. (2006). O Mundo dos Bens: para uma antropologia do consumo. [The World of Goods. Towards an Anthropology of Consumption] Rio de Janeiro: Editora UFRJ.

Douglas, M. (2007). O mundo dos bens: vinte anos depois [The World of Goods: twenty years later], Horizontes Antropológicos, Belo Horizonte, 13(28), 17-32. Retrieved from: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/ha/v13n28/a02v1328.pdf

Fracalanza, P. S. (2000). Regulamentações sobre o Tempo de Trabalho: as 35 horas na França e comentários sobre a situação brasileira. [Regulations on the Working Time: 35 hours in France, and comments on the Brazilian situation] Indicadores Econômicos FEE, Porto Alegre, 28(2), 182-201. Retrieved from: http://revistas.fee.tche.br/index.php/indicadores/article/viewFile/1683/2049

Frank, R. H. (2008). Context is More Important than Keynes Realized. In L. Pecchi & G. Piga (Eds.), Revisiting Keynes: Economic Possibilities for Our Grandchildren (pp. 143-150). Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Freyssinet, J. (1997). Le temps de travail en miettes: 20 ans de politique de l'emploi et de négociation collective. [Working time crumbled: 20 years of employment policy and collective bargaining ] Paris: Les Editions de l'Atelier.

Galbraith, J. K. (1988). O Novo Estado Industrial. [The New Industrial State] São Paulo: Nova Cultural.

Galbraith, J. K. (1999). The Affluent Society. London: Penguin Books.

Gorz, A. (2007). Metamorfoses do Trabalho: crítica da razão econômica. [Metamorphosis of Labor: Critique of Economic Reason] São Paulo: Annablume.

Huberman, M. (2002). Working Hours of the World Unite? New international evidence on worktime – 1870 – 2000. Montreal: Scientific Series. Retrieved from: http://ideas.repec.org/e/phu57.html

Jackson, T. (2010). Prosperité Sans Croissance. [Prosperity Without Growth] Bruxelles: Éditions de Boeck Université.

Keynes, J. M. (2008). Economic Possibilities for Our Grandchildren. In L. Pecchi & G. Piga (Eds.), Revisiting Keynes: Economic Possibilities for Our Grandchildren (pp. 17-26). Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Keynes, J. M. (2013). The Economic Consequences of the Peace. The Project Gutenberg eBook. Retrieved from: http://www.gutenberg.org/files/15776/15776-h/15776-h.htm

Lafargue, P. (1883). The Right to be Lazy. Chicago: Charles Kerr & Company. Retrieved from: http://www.marxists.org/archive/lafargue/1883/lazy/index.htm

Lafargue, P. (1965). Le Droit à la Paresse. [The Right to be Lazy] Paris: Librairie François Maspero.

Landes, D. S. (2003). The unbound Prometheus: technological change and industrial development in Western Europe from 1750 to the present. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lee, S.; McCann, D. & Messenger, J. C. (2007). Working Time Around the World: trends in working hours. New York: Routledge.

Lipovetsky, G. & Roux, E. (2005). O Luxo Eterno: da idade do sagrado ao tempo das marcas. [The eternal luxury: From the age of the sacred to the time of the brand] São Paulo: Companhia das Letras.

Lipovetsky, G. (2007). A Felicidade Paradoxal: ensaio sobre a sociedade de hiperconsumo. [Paradoxical Happiness: an essay on the hyperconsumption society] São Paulo: Companhia das Letras.

Manning, R. D. (2000). Credit Card Nation: the consequences of America’s addiction to credit. New York: Basic Books.

Marx, K. (1909). Capital: a critique of political economy. Chicago: Charles H. Kerr & Company.

Packard, V. (2007). The Hidden Persuaders. Canada: Ig Publishing.

Pecchi, L. & Piga, G. (Eds.). (2008). Revisiting Keynes: Economic Possibilities for Our Grandchildren. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Russell, B. (1932). In Praise of Idleness. Retrieved from: http://prdupl02.ynet.co.il/ForumFiles_3/31164247.pdf

Schor, J. (1992). The Overworked American: The Unexpected Decline of Leisure. New York: Basic Books.

Schor, J. (2010). Plenitude. New York: Penguin Group.

Schumpeter, J. A. (2003) Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy. London & New York: Routledge.

Skidelsky, R. & Skidelsky, E. (2012). How Much is Enough? New York: Other

Skidelsky, R. (2009). Keynes: the return of the master. London, UK: Penguin Books.

This research was supported mainly by a grant from the Sao Paulo Research Foundation - FAPESP [FAP - 09/16647-8].

1. PhD in Economics. Researcher at the Center for Industrial Economics and Technology (NEIT) and the Centre for Trade Union and Labor Studies (CESIT), both at UNICAMP. Currently, he is Professor and Director of the Institute of Economics of the State University of Campinas. fracalan@gmail.com

2. PhD in Science and Technology Policies. Researcher, Assistant Professor and Supervisor at Science and Technology Policies Graduate Program at the Geosciences Institute of the State University of Campinas - UNICAMP. rosanacorazza@ige.unicamp.br