Vol. 38 (Nº 33) Año 2017. Pág. 9

Vilena Yuryevna ZHILENKO 1; Marina Evgenievna KOMAROVA 2; Svetlana Nikolaevna YASENOK 3; Inna Sergeevna KOROLEVA 4; Irina Vladimirovna SEMCHENKO 5

Received: 20/05/2017 • Approved: 01/06/2017

ABSTRACT: The paper presents the research on the development of ecological tourism in Ireland. The basic directions and problems of development of ecotourism. Income from ecotourism in the country was analyzed in the article, as well as the model for the attraction of tourists to Ireland. Ecotourism in Ireland is one of the most influential spheres of life. The main objects of ecological tourism in Ireland, which attract significant flows of tourists, are: Dublin Zoo (located in Dublin, 1,076,876 tourists), National Botanic Gardens (located in Dublin, 541,946 tourists), Doneraile Wildlife Park (located in Cork, 460,000 tourists), Tayto Park (located in Meath, 450,000 tourists), Fota Wildlife Park (located in Cork, 438,000 tourists). |

RESUMEN: El artículo presenta la investigación sobre el desarrollo del turismo ecológico en Irlanda. Las direcciones básicas y los problemas de desarrollo del ecoturismo. Los ingresos del ecoturismo en el país fueron analizados en el artículo, así como el modelo para la atracción de turistas a Irlanda. El ecoturismo en Irlanda es una de las esferas de vida más influyentes. Los principales objetos del turismo ecológico en Irlanda, que atraen importantes flujos de turistas, son: el zoológico de Dublín (situado en Dublín, 1.076.876 turistas), el Jardín Botánico Nacional (situado en Dublín, 541.946 turistas), el Parque Natural de Doneraile (situado en Cork, 460.000 Turistas), Tayto Park (ubicado en Meath, 450.000 turistas), Fota Wildlife Park (ubicado en Cork, 438.000 turistas). |

Ecotourism is one of the most rapidly growing sectors in the global tourism industry. The first condition of ecological tourism, which makes it different from the previously used forms of organization and spending a relaxing holiday, is sensible, environmentally and economically verified policy in the use of resources, as well as recreational areas, development and compliance of the "no depleted" nature, which is designed to ensure not only the conservation of biological diversity of recreation areas, but also the stability of the most popular tourist activities.

The World Tourism Organization (WTO) defines trends in the development of ecotourism. According to the WTO forecasts, the environmental tourism is among the five main strategic directions of development of tourism for the period up to 2020.

Ecotourism is a sector which is steadily gaining significant credibility within the tourism industry in Ireland. The core ethos and principles of the ecotourism sector are also beginning to permeate mainstream tourism businesses in response to increasing demand by tourists and the cost savings that can be made by ‘going green’. Fáilte Ireland has long held the belief that the future sustainability of our tourism industry depends on the extent to which we protect the credibility of our clean green image. It is also important that visitors to Ireland are given options to reduce the carbon footprint of their holiday. With an increase in the levels of good environmental practice in the tourism sector in recent years, Ireland is in a better position than ever to offer choices to visitors wishing to have a lower emissions holiday (Ecotourism hand book for Ireland, 2012).

Vijai Kaprihan (2004) pointed out that ecotourism is an amalgamation of two separate ecology and tourism concepts, but viewed jointly the coinage assumes great significance - both for ecological conservation and development of tourism. Ecotourism ensures satisfaction and is conducted for small homogeneous groups.

Jagmohan (1999) conducts a study about ecotourism planning. He says that “all the stakeholders in tourism development should safeguard the natural environment with a view to achieving sound, continuous and sustainable economic growth geared to satisfying equitably the needs and aspirants of present and future generations”.

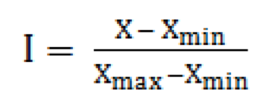

Water, forest resources and objects of specially protected natural territories were assessed to identify security targets of eco-tourism areas of Ireland. In assessing water resources, the value and importance of recreational water bodies (expert evaluation in points) were taken into account. At Woodland analysis, forest cover area was taken into account. In the analysis of protected areas, the area of specially protected natural areas (in terms of area of the district) and the status of which is estimated by experts in points were taken into account. These interim indices: water, wood, and security of protected areas. It was calculated by using the following formula:

(1)

(1)

where: I - intermediate index for each indicator;

X - absolute value of one of the indicators.

The index value of I varies from 0 to 1. It shows the location of the index of each area of security among all the other areas.

He calculated intermediate indexes on key indicators that had been adjusted by means of additional factors. The main component of the integrated assessment was adopted by the proportion of specially protected natural area on the area of the region and the status of specially protected area in points. Because of its correction factor was 0.5, while the each coefficient of other two blocks was 0.25.

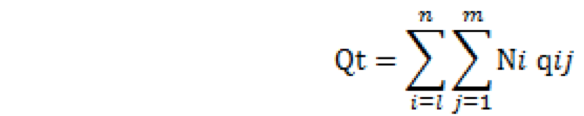

For the classification and mapping of evaluation results integral index was calculated, which is the sum of intermediate indexes based on the correction factors:

![]() (2)

(2)

I1 - intermediate index of security of protected areas;

I2, І3 - interim security codes of forest and water resources;

0.5 - correction factor of security of protected areas;

0.25 - correction factors of security of forest and water resources.

The mild oceanic climate, low mountains and the absence of sudden changes in temperature ensure lush vegetation on the island. Up until the 17th century, thick forests covered most of the area of Ireland, but now, as a result of human activity, virtually all forests are deforested.

The results showed that the maximum integral index has Killarney National Park. The Killarney National Park includes unique yew forests and groves of ancient oaks.

Thus, the national park may become a priority target for ecotourists.

Tourists’ expenditure during their visits of Ireland (including receipts paid to Irish carriers by foreign visitors) was estimated to be worth €5.1 billion in 2014, this represents growth of 10%. Combining spending by international tourists with the money spent by Irish residents taking trips here, total tourism expenditure in 2014 was estimated to be €6.6 billion (Tourism facts 2014 - Failte Ireland).

Attendance at popular visitor attractions in Ireland 2014 involves mainly national parks, botanical gardens and zoos, these tourist attractions occupy the first place in the ranking of the tourists, indicating the intensive development of ecotourism in Ireland (table 1).

Table 1. Attendance at popular visitor attractions in Ireland 2014

Top Fee-Charging Attractions* |

Top Free Attractions |

||||

Name of Attraction |

County |

2014 |

Name of Attraction |

County |

2014 |

Guinness |

Dublin |

1,269,371 |

The National Gallery of Ireland |

Dublin |

593,183 |

Cliffs of Moher Visitor Experience |

Clare |

1,080,501 |

National Botanic Gardens |

Dublin |

541,946 |

Dublin Zoo |

Dublin |

1,076,876 |

Doneraile Wildlife Park |

Cork |

460,000 |

National Aquatic Centre |

Dublin |

931,074 |

National Museum of Ireland - Archaeology, Kildare S |

Dublin |

447,137 |

Book of Kells |

Dublin |

650,476 |

Science Gallery at Trinity College Dublin |

Dublin |

406,982 |

St Patrick’s Cathedral |

Dublin |

457,277 |

Farmleigh |

Dublin |

402,773 |

Tayto Park |

Meath |

450,000 |

Newbridge Silverware |

Kildare |

350,000 |

Fota Wildlife Park |

Cork |

438,000 |

Irish Museum of Modern Art |

Dublin |

306,662 |

Blarney Castle |

Cork |

390,000 |

Chester Beatty Library |

Dublin |

304,000 |

Rock of Cashel |

Tipperary |

372,503 |

National Museum of Ireland - Natural History, Merrion St |

Dublin |

300,272 |

Kilmainham Gaol |

Dublin |

328,886 |

The National Library of Ireland |

Dublin |

270,394 |

Bunratty Castle & Folk Park |

Clare |

294,339 |

National Museum of Ireland - Decorative Arts & History, Collins Barracks |

Dublin |

243,172 |

Castletown House & Parklands |

Kildare |

285,410 |

Holy Cross Abbey |

Tipperary |

200,000 |

Old Jameson Distillery |

Dublin |

270,038 |

Connemara National Park |

Galway |

169,960 |

Kilkenny Castle |

Kilkenny |

259,250 |

Dublin City Gallery – The Hugh Lane |

Dublin |

160,000 |

Powerscourt House & Gardens |

Wicklow |

232,605 |

Galway City Museum |

Galway |

153,000 |

Dublin Castle |

Dublin |

217,758 |

Nicholas Mosse Pottery |

Kilkenny |

120,000 |

Christ Church Cathedral |

Dublin |

173,265 |

Sliabh Liag Cliffs |

Donegal |

120,000 |

Glenveagh National Park, Castle & Gardens |

Donegal |

150,691 |

National Museum of Ireland - Country Life, Turlough Park |

Mayo |

109,000 |

Clonmacnoise |

Offaly |

149,472 |

Malin Head Viewing Point |

Donegal |

105,000 |

Dublinia |

Dublin |

149,347 |

The Model |

Sligo |

104,000 |

Source: Fáilte Ireland Visitor Attraction Survey 2014

*Revised February 2016

The main objects of ecological tourism in Ireland are such objects as Dublin Zoo (located in Dublin, 1,076,876 tourists), National Botanic Gardens (located in Dublin, 541,946 tourists), Doneraile Wildlife Park (located in Cork, 460,000 tourists), Tayto Park (located in Meath, 450,000 tourists), Fota Wildlife Park (located in Cork, 438,000 tourists).

The decisive condition for the development of tourism is the state of the demographic situation in the country, the standard of living of the population, conditions of reproduction or replenishment of structural and numerical composition of the population. In Ireland, these questions become particularly acute, since most of the income of the population was higher than the subsistence minimum.

It is essential to value the factor of free time. Only the presence of free time allows you to navigate on-site living conditions - in weekend mode, week and longer vacations. The theoretical premise of using spare time as a major factor in determining the direction of its structural implementation allows to approach and to solve the pragmatic problem - community participation in the tourism sector.

This task is defined by us as follows (1):

(3)

(3)

where: Qt - the number of tourists in the tourist service;

Ni - contingent;

i - population;

qij - participation rate;

i – contingent population;

j- tourist areas of participation.

The basic principles of development of ecological tourism are:

- The conservation of biodiversity of ecosystems in accordance with the requirements and standards of the legal framework in the field of tourism, environmental law, nature conservation and environmental management;

- Improving the economic sustainability of ecotourism zone - the creation of new jobs and additional sources of income for local people, to identify ways to optimize the development of local industries, involvement of the local population to cooperate the organizations, and management of eco-tourism;

- Environmental education and education, raising the level of ecological culture of ecotourists and members of ecotourism activities, introduction of principles of sustainable development in education through the formation of ecological outlook and ecological culture;

- Ensuring the preservation of social and cultural diversity, that is, respect of local traditions, customs and practices, careful recourse to the culture of the indigenous population, the growth of intercultural understanding, the creation of social structures and institutions, conservation of ethnographic recreation area, education of responsible and patriotic attitude to their own natural and cultural heritage.

There is a large number of objects that include exploration of the touristic areas. These include a variety of natural and natural and cultural sites, including:

• The most popular and notable species (flora and fauna), the so-called types - flagships, endemic and relict species;

• unique objects and phenomena of inanimate nature (geological, geomorphological, hydrological and other elements of the landscape);

• exotic plant communities and ecological communities;

• career where you can make the paleontological, petrological, botanical and other findings for the collection;

• natural and anthropogenic (cultural) landscapes as a whole, also located within the cultural, ethnographic, archaeological, historical and memorial objects.

In Ireland, there are plenty of ideal places for ecotourism. The most famous and beautiful resorts of this type include the following areas: Donegal, County Sligo, Beech Alley, Valley of Delphi, Trail of Giants, Cliffs of Moher, Cape Downpatrick Head, Amazing Granary, Aran Islands, Big Island Salt.

This article concludes that Ireland is a country with a rapidly growing sector of the tourism industry. There are a lot of greenery on the island, the climate is temperate oceanic, humid mild winters, cool summers. Thanks to the mild climate Ireland is covered by greenery all year, that is why it is known as the Emerald Isle.

There are many national parks, botanical gardens, zoos on the territory of Ireland, so that the ecological tourism are developing rapidly.

A large number of tourist attractions, according to statistics on territory eco-tourism facilities, visit Dublin Zoo (located in Dublin, 1,076,876 tourists), National Botanic Gardens (located in Dublin, 541,946 tourists), Doneraile Wildlife Park (located in Cork, 460,000 tourists), Tayto Park (located in Meath, 450,000 tourists), Fota Wildlife Park (located in Cork, 438,000 tourists).

In the east, Ireland is washed by the Irish Sea and the straits of St. George in the North, from the west, north and south sides - by Atlantic Ocean. Dolphins inhabit Irish waters; there are many dolphins especially in County Cork. According to the data of 2014, dolphins in County Cork floated under the water with wet suited tourists, but dolphins, unlike sharks, do not attack the victims.

No less valuable objects of ecological tourism are Donegal, County Sligo, Beech Alley, Valley of Delphi, Trail of Giants, Cliffs of Moher, Cape Downpatrick Head, Amazing Granary, Aran Islands, Big Island Salt (Wendy F. Walsh and E. Charles Nelson, 2009; Jones, S, 2005; Laiola, P, 2003; Avila Foucat, V.S, 2002; Dyck, M.G. and Baydack, R.K., 2004; Lepp, A., 2007).

According to the investigations conducted by the value of environmental facilities for tourists on the integral indicator, the most significant indicator has Killarney National Park.

Thus, for the sustainable development of tourism in the Emerald Isle it is necessary to develop ecological tours, conduct public relations activities and promotion of Irish tourist product worldwide. Ireland attractions are certainly of considerable tourist interest. Ecological tours may be used as cognitive, educational and scientific resources.

Avila Foucat, V.S. (2002). Look at Community-based ecotourism management moving towards sustainability, in Ventanilla, Oaxaca, Mexico. Ocean and Coastal Management, 45: 511-529.

Caprihan, V. and Shivakumar, K. (2004). “Eco - Tourism in India”. South Asian Journal of Socio-Political Studies (SAJOSPS), 12(2): 80-85.

Ecotourism hand book for Ireland, (2012). Date Views 20.12.2016 http://www.failteireland.ie/FailteIreland/media/WebsiteStructure/Documents/2_Develop_Your_Business/1_StartGrow_Your_Business/Ecotourism_Handbook-2.pdf.

Dyck, M.G. and Baydack, R.K. (2004). Vigilance behaviour of polar bears (Ursus maritimus) in the context of wildlife-viewing activities at Churchill, Manitoba, Canada. Biological Conservation, 116 (3): 343 –350.

Jones, S. (2005). Community-based ecotourism: The significance of Social Capital. Annals of Tourism Research, 32 (2): 303-324.

Laiola, P. (2003). Diversity and structure of the bird community overwintering in the Himalayan subalpine zone: is conservation compatible with tourism? Biological Conservation 15: 251-262.

Lepp, A. (2007). Resident’s attitudes towards tourism in Bigodi village, Uganda. Tourism Management, 28: 876-885.

Negi, J. (1999). Tourism Travel - Concepts and Principles. New Delhi: Gitanjali Publishing House, pp. 64-77.

Tourism facts 2014 - Failte Ireland. (n. d.). Date Views 20.12.2016 http://www.failteireland.ie/FailteIreland/media/WebsiteStructure/Documents/3_Research_Insights/3_General_SurveysReports/Tourism-facts-2014.pdf.

Walsh, F. W. and Nelson, E. C. (2009). The Wild and Garden Plants of Ireland. United Kingdom: Edité par Thames Hudson Ltd, pp. 224.

1. Belgorod National Research University, 308015, Belgorod region, Belgorod, st. Pobedy, 85. Email: vilena33@mail.ru

2. Belgorod National Research University, 308015, Belgorod region, Belgorod, st. Pobedy, 85

3. Belgorod National Research University, 308015, Belgorod region, Belgorod, st. Pobedy, 85

4. Belgorod National Research University, 308015, Belgorod region, Belgorod, st. Pobedy, 85

5. Belgorod National Research University, 308015, Belgorod region, Belgorod, st. Pobedy, 85