HOME | ÍNDICE POR TÍTULO | NORMAS PUBLICACIÓN

HOME | ÍNDICE POR TÍTULO | NORMAS PUBLICACIÓN Espacios. Vol. 37 (Nº 23) Año 2016. Pág. 25

Roberta de Castro SOUZA Pião 1; Gabriela SCUR 2; Patrícia BELFIORE Favero 3; João CHANG Jr 4

Recibido: 07/04/16 • Aprobado: 23/05/2016

ABSTRACT: It is well known the importance of retailer's requirements and their effect on the structure of supply chains. However, it is still under investigation the group of patterns defined by different types of retailers and their impacts on the structure of fresh food supply chains, mainly in developing countries. The paper investigates the elements considered for different retail formats in their selection of tomato and lettuce suppliers in the city of São Paulo, Brazil. Regarding the empirical research, it was carried out face to face interviews with retailers. The findings indicate that large supermarkets chains are stricter than other types of retailers investigated. |

RESUMO: A importância dos requisitos dos varejistas e seu efeito na estrutura da cadeia de suprimentos é bem conhecida. Entretanto, ainda está sob investigação os grupos de padrões definidos pelos diferentes tipos de varejo e seus impactos na estrutura da cadeia de suprimentos de produtos frescos, especialmente em países em desenvolvimento. Este artigo investiga os elementos considerados pelos diferentes formatos na seleção de fornecedores de tomate e alface na cidade de São Paulo, Brasil. Considerando a pesquisa empírica, foram realizadas entrevistas face-a-face com os varejistas. Os resultados indicam que as grandes cadeias de supermercados são mais rígidas que outros tipos de varejo investigados. |

The competitiveness of firms depends on their capability to produce and deliver customized products and services fast and efficiently. In this context, the value creation is taking place outside the boundaries of the individual firms. This new configuration promotes higher complexity and diversity into management decisions and new forms of collaboration between all members in the transformation chain named as a supply chain (HALLDORSSON, KOTZAB and LARSEN, 2007).

So, in this study the context is the importance of retailers in the supply chain of fresh food. In general terms, it is well known the importance of retailer's requirements and their effect on the structure of supply chains. However, it is still under investigation the group of patterns defined by different types of retailers and their impacts on the structure of fresh food supply chains, mainly in developing countries.

As theoretical background it is utilized the supply chain theory for promoting insights about the structure of tomato and lettuce supply chain as well as the value added at different stages of these chains (RUBEN, BOSELIE, LU, 2007). Regarding the empirical research, it was carried out face to face interviews with retailers located in the city of Sao Paulo.

The term supply chain (SC) is defined by Mentzer et al. (2001, p. 4) "as a set of three or more entities (organizations or individuals) directly involved in the upstream and downstream flows of products, services, finances, and/or information from a source to a customer". It is important to point out that supply chain as a phenomenon of business exists whether they managed or not. Nevertheless, since the supply has become globalized, the firms have forced to search effective ways to coordinate the flow of materials into and out firms.

Reviewing the literature, we can see that some authors define SC in operational terms involving the flow of materials and products, some view it as a management philosophy and some view in terms of a management process. In all the concepts the SC involves multiple firms and business activities and the coordination of those activities across functions and across firms in the supply chain.

In this paper we have adopted the concept of SC that is defined as the systemic, strategic coordination of the traditional business functions and the tactics across these business functions within a particular firm and across business within the supply chain, for the purposes of improving the long-term performance of the individual firms and the supply chain as a whole (MENTZER ET AL., 2001, p. 18).

Once the importance of the suppliers grows in the supply chain the supplier selection and purchasing decision have become key strategic considerations because it significantly reduces the unit prices and improves corporate price competitiveness (TING, CHO, 2008). In addition, more important it becomes in the agrifood chain since attributes as freshness, colorful, safety, quality are difficult standardize.

Ruben, Boselie and Lu (2007) classified 5 dimensions of analysis of vegetables procurement regimes in Bangkok and Nanjing. The first one is fixed investments represented by quality and freshness, lead-time, out-of-stock and yield loss. The second dimension is variable costs as number of suppliers and distribution costs. The third is economies of scale, fourth is governance costs composed by contractual arrangements, information and search, screening and monitoring, quality control system, quality control, negotiation and enforcement. The fifth dimension is opportunistic behavior measured by asset specificity and risk.

Ting and Cho (2008) argue that there could be several criteria used in the supplier selection process such as price, quality, on time delivery, after sales services, response to order chance, supplier location and their financial status. Thereby, supplier selection is a multi-criteria problem which includes both qualitative and quantitative factors.

One of the most essential food product characteristics to be considered in the performance of the supply chain is maintaining high food quality which degrades depending on environmental conditions of storage and transportation. Apart from being a performance measure of its own, fresh vegetable quality is directly related to other food attributes such as integrity, safety and shelf life and it requires high frequency, constant delivery and stable quality (RONG, 2009).

One way to guarantee the standards of quality and safety and reduce the risks in the agrifood chain is to create private food assurance systems. According to Mondelaers and Van Huylenbroeck (2008) standards can be used to regulate both intrinsic such as product safety and health and extrinsic like production system and environmental related quality attributes. However, these standards will be used according the kind of the transactions, if spot market or more closely relationships.

In order to develop long-term relationships among buyers and suppliers the time can be seen as a key factor. The study conducted by White (2000) revealed that fresh produce retailing relationship development is dependent on product and service performance and also on the levels of trust and commitment that are created in the partnership. The four stages identified in the research are: uncommitted, developing, mature and declining. According to respondents of this research each stage is an opportunity to improve one's offering and also cements the relationship more firmly (WHITE, 2000).

For some authors (Pereira and Csillag, 2004) the Brazilian agribusiness has to be supported by chains highly integrated in order to allow better control of the productive process and thus, achieving quality, hygiene, cost decrease reliability sourcing and traceability. The management of agrifood supply chain is receiving attention of the researchers because is complicated by specific product and process characteristics. Quality control is of a specific nature in the case of fresh vegetables since buyers regularly face problems in monitoring the freshness, shelf-life of the produce, control of pesticide and phytosanitary aspects (RUBEN, BOSELIE, LU, 2007).

In this way, according some authors (Nyaga et al., 20210, Lambert et al., 1999), the relationship between buyers and suppliers is shifting to a model in which the cooperation and trust are the basis of the transaction. Petroni and Panciroli (2002) recommend that supplier base should be managed as a portfolio of relationships. According to Petroni and Panciroli (2002) the arm's-length relationships of the past are giving way to closer buyer-supplier cooperation driven by the perception that there are greater benefits to be obtained through such partnerships.

It is important to note that the choice for these different procurement strategies critically depends on differences in competitive relations and supply chain governance regimes (RUBEN, BOSELIE, LU, 2007). According to Humphrey (2007) consumers from different countries associated low quality of fresh vegetables with large stores, such as hypermarkets.

According to Dolan and Humphrey (2000, p.36) "supermarket retailing is characterized by oligopolistic competition" which implies "using product differentiation and heavy advertising as major weapons". This view is challenged by the differences between UK and German supermarkets investigated by Souza (2005) and relates directly to debates on the impact of supermarkets on supply chains in developing countries (Reardon et al., 2003). Then, the focus of this study is to investigate the elements considered for different retail formats in their selection of tomato and lettuce suppliers. Mainville, Reardon and Farina (2008) argue that there are four types of retailers active in São Paulo´s fresh produce markets. They are: (a) large supermarket chains; (b) small and medium supermarkets; (c) discount green groceries specialized in fresh products and, (d) open-air fair vendors. For this study it was investigated only the three first types of retailers mentioned.

Having in mind the theoretical background presented it was established the criteria for selection of fresh vegetables suppliers. It was defined three dimensions and each one is composed of some variables. The three dimensions are: (1) product quality; (2) delivery reliability; (3) financial status. The variables for the first dimension are: features of product in terms of quantity, size and color; and quality regarding production process and for addressing quality patterns and certificates. The variables for second dimension are: delivery time, delivery quantity, frequency, duration of relationship, packaging. The variables for financial status are: payment deadline, investment in storage facilities, investment in transport, investment in information system, investment in storage facilities and operations scale, financial support, sales promoter. The last dimension refers to investments that buyers impose to suppliers mainly. Further there are dichotomous variables such as wholesalers or preferred suppliers, contract or no, multiple or single source. Referring to contract, we argue that the existence of contract is an initiative to decrease uncertainty as well as multiple sources.

For the empirical research were conducted face to face interviews with eight retailers. The retailers were classified according to Mainville, Reardon and Farina (2008) typification mentioned above. It was interviewed one large supermarket chain (A1), four small and medium supermarkets (B1, B2, B3, B4) and three green groceries specialized in fresh products (C1, C2, C3). For each type of retailer, it was considered the lettuce supplier (L) and tomato supplier (T). The data collected of the research regarding dimensions and variables for eight retailers are detailed in table 1 and table 2.

Table 1: Dimensions and variables for the retailers studied

Dimensions |

Variables |

A1 |

B1 |

B2 |

B3 |

B4 |

C1 |

C2 |

C3 |

||||||||

|

|

L |

T |

L |

T |

L |

T |

L |

T |

L |

T |

L |

T |

L |

T |

L |

T |

Product quality |

Product |

10 |

10 |

9 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

Production process |

10 |

10 |

5 |

5 |

4 |

4 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Delivery reliability |

Delivery time |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

Delivery quantity |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

5 |

5 |

|

frequency |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

|

Duration of relationship |

7 |

7 |

10 |

10 |

8 |

8 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Packaging |

10 |

8 |

10 |

5 |

10 |

5 |

8 |

8 |

10 |

10 |

8 |

8 |

8 |

8 |

0 |

0 |

|

Financial Status |

Payment deadline |

10 |

10 |

8 |

8 |

8 |

8 |

8 |

8 |

8 |

8 |

8 |

8 |

8 |

8 |

0 |

0 |

|

Investment in storage facilities |

5 |

5 |

8 |

8 |

8 |

8 |

8 |

8 |

8 |

8 |

8 |

8 |

8 |

8 |

8 |

8 |

|

Investment in transport |

10 |

5 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Investment in information system |

5 |

5 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Investment in operations scale |

10 |

10 |

7 |

7 |

7 |

7 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Financial support |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Sales promoter |

8 |

8 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

7 |

0 |

7 |

7 |

7 |

0 |

7 |

0 |

10 |

10 |

Table 2: Dichotomous variables

|

A1 |

B1 |

B2 |

B3 |

B4 |

C1 |

C2 |

C3 |

||||||||

|

L |

T |

L |

T |

L |

T |

L |

T |

L |

T |

L |

T |

L |

T |

L |

T |

Formal contract |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

Single supplier |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

Multiple suppliers |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

In order to identify the importance of each variable listed in table 1for distinct retail formats it is used the technique called multidimensional scaling (MDS). The MDS is also applied to analyze the relationships between the retailers and their suppliers based on the dichotomous variables listed on table 2.

The multidimensional scaling is a multivariate technique of interdependence that was originated in the late nineteenth century with the development of models in psychology, however, the diffusion of this method to other areas occurred due to the work of Torgerson (1965).

According to Fávero et al. (2009), MDS is appropriate for graphing n elements (or objects) in a space of dimension smaller than the original, taking into account the distance or dissimilarity between the elements. The MDS helps researchers to identify key dimensions inherent to the objects in the study.

In this paper, we study the metric multidimensional scaling that is used in cases where the variables that provide measures of distance or dissimilarity between objects of study are quantitative. Table 1 showed the grades assigned by each retailer (element or object) related to the importance of each variable in the selection of lettuce and tomato suppliers.

Kruskal (1964) proposed a measure of adjustment adequacy to evaluate the distances derived from the dissimilarity of those original data supplied by respondents. This measure, known as Stress (Standardized residual sum of squares) is defined as:

Where f(dij) represents the distances derived from the dissimilarity data and dij the original distances transformed. As higher is the Stress value, worse is the adjustment, since its minimum value is 0 when there are no differences between distances and dissimilarities. Kruskal (1964) suggests that the new Stress measures treated as follow:

The value of SStress ranges from 0 to 1 and, typically, the model adjustment is good when its value is less than 0.1 (Kruskal and Wish, 1978).

Finally, the adjustment quality can also be evaluated using the RSQ index (Root mean SQuare) which represents a quadratic correlation (a measure known as R2) between the original distances provided by the respondents and the distances derived from the data dissimilarity through the MSC, and can be interpreted as the proportion of variance of the dissimilarities, which is explained by the original distances. Thus:

where the subscripts (..) represent the average of the corresponding element to the sub-index and its values range from 0 to 1.

The metric multidimensional scaling is applied from the SPSS software, using the algorithm ALSCAL (Alternating Least Squares Scaling) which is applicable to data with different levels of measurement (metric or non-metric).

Two types of analysis are presented: the first one based on the dimensions and variables listed on table 1 in order to identify the importance of each variable for distinct retail formats; and the second based on the dichotomous variables listed on table 2 in order to analyze the relationships between the retailers and their suppliers.

Through the results presented in table 3, we can affirm that the adjustment quality is excellent for the original data from table 1, according to the criteria suggested by Kruskal (1964).

Table3: Measures of adjustment quality for the original data listed on table 1

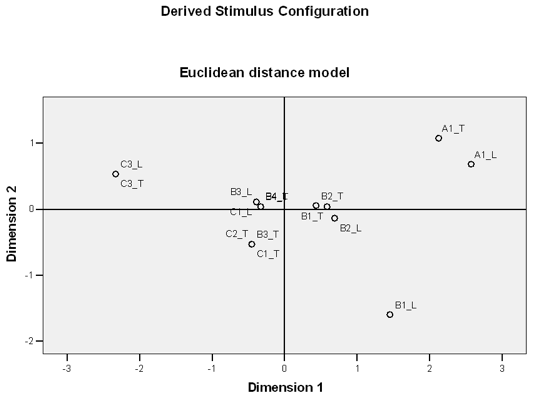

Figure 1 presents the perceptual map of similarity between the retailers studied (from the data presented in table 1) considering a bi-dimensional space.

Analyzing the results from figure 1 and the initial data from table 1 we obtained the significant variables for dimensions 1 and 2. The significant variables for dimension 1 were: production process, delivery quantity, duration relationship, packaging, payment deadline, investment in transport, investment in information system and investment in operations scale. For dimension 2, the significant variable was sales promoter.

Figure 1: Perceptual map of similarity considering the original data from table 1

Two types of analysis were done to interpret the results from figure 1. The first one compares the differences between the relation of lettuce and tomato suppliers with their retailers. The second compares the differences between different types of retailers in the supplier selection.

Firstly, considering the differences between the relation of lettuce and tomato suppliers with their retailers, we conclude that, for most of the variables studied, there is no difference between these two types of suppliers. On the other hand, packaging, investment in transport and sales promoter are important criteria required by the retailers for lettuce suppliers' selection. The same does not happen with tomato suppliers. The first two criteria belong to dimension 1 and the sales promoter criteria to dimension 2. So, we conclude that the distance in the perceptual map (figure 1) between the elements A1L and A1T, B1L and B1T, and B2L and B2T, occurred due to the major importance assigned by these retailers for some variables of dimension 1 (packaging, investment in transport) in the selection of lettuce suppliers.

Secondly, comparing the preferences between different types of retailers, we conclude that large supermarkets (A1) firstly, followed by some of the small and medium supermarkets (B1, B2), considered the significant variables of dimension 1 as important criteria for selection of lettuce and tomato suppliers. On the other hand, one of the discount green groceries specialized in fresh products (C3) assigned minor importance to the variables of dimension 1 in its selection of suppliers. The other types of retailers are very similar for dimension 1. In contrast, you can also see from figure 1 that retailers C3 and A1 are significant for dimension 2, concluding that the criterion sales promoter is an important requirement imposed by these retailers for selection of lettuce and tomato suppliers.

Through the results presented in table 4, we can also affirm that the adjustment quality is excellent for the original data from table 2, according to the criteria suggested by Kruskal (1964).

Table 4: Measures of adjustment quality for the original data listed on table 2

Figure 2 presents the perceptual map of similarity comparing the retailers studied (for the data presented in table 2) considering a bi-dimensional space.

Figure 2: Perceptual map of similarity considering the original data from table 2

We can conclude that the formal contract between retailers and suppliers just happens in the case of large supermarket (A1) and one small retailer (B2), for both lettuce (L) and tomato (T) suppliers.

Besides, most of the retailers of all types (large, medium and small supermarkets, and groceries) and most of products are supplied by intermediary agents in the supply chain. The exception occurs with the retailers B1_T and B2_L which are provided by a single supplier in the supply chain.

Regarding theoretical implications, it is possible to highlight the importance of distinct requirements imposed by different types of retailers. Then the patterns of suppliers' selection depend on the type retailer and this view challenged the literature about supermarkets which generalize the strategies of supermarkets based on preferred suppliers.

The findings indicate that large supermarkets chains are stricter than other types of retailers investigated. On the other hand, small and medium supermarkets, and groceries usually impose to their fresh vegetables suppliers' investments in storage facilities and sales promoter. In addition, for some retailers' requirements, lettuce producers are more prepared to supply. They usually produce different kinds of vegetables, besides lettuce, which shows high diversification. The lettuce suppliers usually wash and pack products addressing retailer's requirements. They also pack with the retail brand and deliver diary in each store.

We can also conclude that the formal contract between retailers and suppliers just happens in the case of large supermarket and one small retailer. Besides, most of the retailers, considering different types of products, are supplied by intermediary agents in the supply chain.

We are thankful to FAPESP – São Paulo Research Foundation for supporting and funding this research.

DOLAN, C. and HUMPHREY, J. (2000) Governance and trade in fresh vegetables: the impact of UK supermarkets on the African horticulture industry, Journal of Development Studies, v.37, n.2, pp.1-37.

FÁVERO, L.P.; BELFIORE, P.; SILVA, F.L. CHAN, B.L. (2009) Análise de dados: modelagem multivariada para tomada de decisões. Rio de Janeiro: Campus, 2009.

HALLDORSSON, A.; KOTZAB, J.; LARSEN, T. (2007) Complementary theories to supply chain management, Supply chain management: an international journal, vol. 12, no. 04, p. 284-296.

HUMPHREY, J. (2007) The supermarket revolution in developing countries: tidal wave or tough competitive struggle? Journal of Economic Geography, 7, p. 433-450.

KRUSKAL, J. B. (1964). Multidimensional scaling by optimizing goodness of fit to a nonmetric hypothesis, Psychometrika, v. 29, n. 1, pp. 1-27.

KRUSKAL, J. B.; WISH, M. (1978) Multidimensional scaling. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications.

LAMBERT, D. M.; EMMELHAINZ, M. A.; GARDNER, J. T. (1999) Building successful logistics partnerships. Journal of Business Logistics, v. 20, n. 1, p. 165-180.

MAINVILLE, D.Y.; REARDON, T.; FARINA, E.M.M.Q. (2008) Scale, scope, and specialization effects on etailers' procurement strategies: evidence from the fresh produce markets of São Paulo. Revista de Economia e Sociologia Rural, v.46, n.01, Jan./Mar.

MENTZER, J; DEWITT, W.; KEEBLER, J.; MIN, S; NIX, N; SMITH, C; ZACHARIA, Z. (2001). Defining Supply Chain Management, Journal of Business Logistics, vol.22, no. 02.

METCALF, L.,FREAR, C.,KIRSHNAN, R. (1992) Buyer–seller relationships an application of the IMP interaction model. ,European Journal of Marketing 26 (2), 27–46.

NYAGA, G. N.; WHIPPLE, J. M.; LYNCH, D. F. (2010) Examining supply chain relationships: do buyer and supplier perspectives on collaborative relationships differ? Journal of Operations Management, v. 28, p. 101-104.

PEREIRA, S., CSILLAG, J. (2004). Performance Measurement Systems: consideration of an agrifood supply chain in Brazil, Proceedings of the 2nd World conference and 15th Annual Conference. Cancun, México.

PETRONI, A.; PANCIROLI, B. (2002). Innovation as a determinant of suppliers' roles and performances: an empirical study in the food machinery industry.European Journal of Purchasing & Supply Management, 8(3), 135-149.

REARDON, T., TIMMER, P., BARRETT, C.; BERDEGUÉ, J. (2003). The rise of supermarkets in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, v. 85, n.5, pp.1140-1146.

RONG, A., AKKERMAN, R.; GRUNOW, M. (2011). An optimization approach for managing fresh food quality throughout the supply chain. International Journal of Production Economics, 131(1), 421-429.

RUBEN, R., BOSELIE, D., LU, H. (2007). Vegetables Procurement by Asian supermarkets: a transaction cost approach, Supply Chain Management: an International Journal. No. 12, vol, 1, pp. 60-68.

SHAW, S.; GIBBS, J. (1996). The role of marketing channels in the determination of horizontal marketing structure: the case of fruit and vegetable marketing by British growers, The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research,v. 6, no. 3, pp. 281-300.

SOUZA, R. C. (2005) Uma investigação sobre o segmento produtor de manga e uva in natura em sua inserção na cadeia de valor global. PhD thesis. Department of Production Engineering, University of São Paulo, 197 p.

SOUZA, R.C.; AMATO, J. (2009). As transações entre supermercados europeus e produtores brasileiros de frutas frescas, Revista Gestão & Produção, v.16, n.3, pp. 489-501.

SOUZA, R.C., SCUR, G. (2010) As transações entre varejistas e fornecedores de frutas, legumes e verduras na cidade de São Paulo, Production, vol. 21, n. 3, pp. 518-527.

TING, S.; CHO, D. (2008). An Integrated Approach for Supplier Selection and Purchasing Decisions. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, v. 13, no. 2, pp. 116-127.

TORGERSON, W. S. (1965). Multidimensional scaling of similarity,Psychometrika, v. 30, n. 4, pp. 379-393.

WHITE, H. (2000). Buyer-supplier relationships in the UK fresh produce industry. British Food Journal, Bradford: 2000, vol. 102, iss. 1, p. 6-13.

1. Assistant Professor at the Department of Production Engineering in the University of São Paulo, Brazil. Degree in Economics (1995), a Master's in Production Engineering (1999) and a PhD in Production Engineering at the University of São Paulo, Brazil (2005). Besides, I was a visiting fellow at the University of Sussex, the Institute of Development Studies (IDS), United Kingdom, in 2004. Has experience in global value chains, agrifood, sustainable chains

2. Adjunct Professor at Department of Production Engineering in the University of FEI, Brazil. She is currently Associate Professor in the Master's Program in Engineering Mechanics at FEI University. Degree in Business (1997), a Master's in Business (2000) and a PhD in Production Engineering at the University of São Paulo, Brazil (2005). Besides, I was a visiting fellow at the University of Padua, the Institute of Economics, Italy, in 2005. Has experience in innovation, sustainability and operations strategy. Email: gabriela@fei.edu.br

3. Post-Doc in Operational Research from Columbia University, New York (2009). graduate at Production Engineering from University of FEI (1998), masters at Electric Engineering from University of São Paulo (2003). Professor at Federal University of ABC. Has experience in Production Engineering, focusing on Planning, Project and Control of Systems of Production

4. Postdoctoral Program in Business Administration at University of São Paulo (2006). PhD in Business Administration from University of São Paulo (2001). Completed the Master's Program in Quality at University of Campinas (1995). He graduated in Mechanical Engineering at University of Santa Cecilia (1984) and Electrical Engineering at University of São Paulo (1978). He is currently Associate Professor in the Master's Program in Engineering Mechanics at FEI University, Full Professor at "Fundação Armando Alvares Penteado", Full Professor at "Escola Superior de Engenharia e Gestão - ESEG". He has experience in the areas of Enterprise and Production Engineering Management, with emphasis on Quantitative Methods, acting on the following topics: Multivariate Statistics, Operations Research, Theory of Decision Making, Quality in Health Institutions.